The Battle of Blair Mountain

June 30, 2010

Following a wave of strikes, by 1920 the United Mine Workers (UMW) had succeeded in winning union contracts for miners across much of the nation, but coal barons in the southern West Virginia were determined to keep workers down. Company bosses cut their pay, raised prices in company stores, and hired spies and armed agents to intimidate them. Aided by corrupt state and local officials, they brutally oppressed 50,000 miners and stopped at nothing to defeat union organizing efforts.

The miners’ struggle for safe working conditions, better pay, and union rights led to a bloody showdown with company thugs in Matewan, WV in May 1920. (See May/June 2010 American Postal Worker.) The subsequent assassination of Police Chief Sid Hatfield, a miners’ hero, sparked the Battle of Blair Mountain — the largest armed uprising in the U.S. since the Civil War.

News of Hatfield’s murder by coal company agents on Aug. 1, 1921, spread like wildfire across southern West Virginia’s coal mines.

News of Hatfield’s murder by coal company agents on Aug. 1, 1921, spread like wildfire across southern West Virginia’s coal mines.

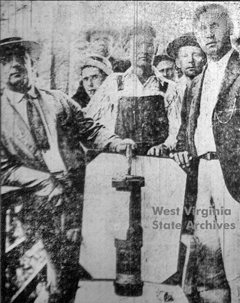

Thousands of miners gathered for a rally at the state capital in Charleston on Aug. 7, where UMW leaders Frank Keeney and Bill Blizzard called for an army of workers to march through three counties to drive out company gunmen. Keeney spent two weeks recruiting volunteers for a march to Logan County, a coal company stronghold.

Meanwhile, “The Logan Coal Operators Association paid Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin to keep union organizers out of the area,” notes an article in the West Virginia state archives. “Chafin and his deputies harassed, beat, and arrested those suspected of participating in labor meetings.”

Thousands of miners from across the state began assembling near Charleston on Aug. 20 for the 65-mile march to Logan County. The march began on Aug. 24, and as many as 20,000 miners joined their ranks along the way.

But the coal barons and Sheriff Chafin were ready for the protestors. A heavily armed, well-entrenched, hired militia of 3,000 occupied strategic points high on Blair Mountain, a natural defensive barrier guarding the county seat. Chafin had amassed an arsenal of weapons including machine guns and landmines, and created an air force of private planes to monitor the miners’ approach. Gov. Ephraim Morgan declared martial law and dispatched state police and an unofficial West Virginia guard unit to aid the sheriff ’s forces.

The miners were well organized, too. In military fashion (many were World War I veterans) they appointed leaders, and arranged transportation for additional recruits and supplies. Lacking uniforms, they wore red bandanas to distinguish themselves from company gunmen, who wore white patches. (The miners began to refer to themselves as “rednecks,” and a new term was added to the American lexicon.) To guard against spies, the miners created passwords that were never revealed, even decades after the conflict.

The first skirmishes took place on Aug. 25 on the outskirts of Logan, and Gov. Morgan quickly asked President Warren Harding to send federal troops to help stop the uprising.

Federal Threat

Harding sent Gen. Henry Bandholtz to survey the situation. When he arrived in Charleston on Aug. 26, Bandholtz told the governor and UMW leaders that he intended to restore order immediately. He warned the union leaders that if the marchers did not turn back, the U.S. Army would “snuff them out” or arrest them for treason. Fearing disaster, legendary union organizer Mother Jones and other national UMW officials urged the miners to call off the march.

That afternoon, UMW leader Keeney relayed Gen. Bandholtz’s threats to a large group of miners at a ball field in Boone County, and convinced them to turn back. They had come to stand up to the coal bosses, they reasoned, not to fight the U.S. army.

Bandholtz had assured Keeney that he would not allow the militias to pursue them, notes historian Clayton D. Laurie, and the marchers made arrangements with local railroads to return to their homes the next day.

Turning Point

But the coal companies had sent in thousands of reinforcements, and Chafin was determined to end union organizing in Logan County while he felt he held the advantage.

On the night of Aug. 27, soon after miners began leaving the scene, reports came in that “Chafin’s forces were deliberately shooting union sympathizers in the town of Sharples, just north of Blair Mountain—and that families had been caught in crossfire.”

Infuriated, the miners turned back — some traveling in commandeered trains — to confront Chafin’s forces, and the battle was on. On Aug. 28, union forces captured four deputies. Three days later, a small armed company of Logan residents organized by a local Baptist minister killed three others.Chafin’s planes dropped homemade bleach and shrapnel bombs, but failed to intimidate the union forces. Many thousands of rounds were fired by both sides, as the miners attempted to storm the hill.

At Bandholtz’s request, President Harding sent federal troops to end the confrontation. Several thousand soldiers arrived by Sept. 3, along with an air squadron armed with bombs and gas.

Unwilling to fight the U.S. Army, the miners laid down their arms and returned home. Chafin’s forces also obeyed Bandholtz’s order to disband.

Aftermath

Several hundred combatants were wounded during the fighting and 16 were killed, including 12miners and four of Chafin’s men. Gov. Morgan tried to persuade the Army to help civil authorities arrest miners, but Bandholtz refused.

West Virginia courts indicted 1,217 suspected leaders of the rebellion but charges were later dropped against all but one, who fled the state and was convicted in absentia. The local minister and his son were convicted of murder, but both were pardoned by Gov. Howard Gore after serving three years in prison. Chafin was arrested several years later on corruption charges and served time in federal prison for bootlegging.

Although the miners’ march failed to unionize southern West Virginia coal mines, their plight garnered worldwide attention and helped build support for the National Labor Relations Act of 1935,which protects workers’ right to form unions and bargain collectively. Generations of American workers have reaped the benefits.

The southern West Virginia coal fields were organized following passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933, another New Deal-era labor reform.