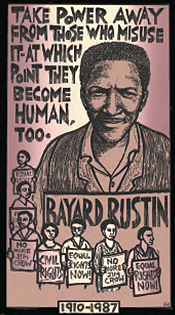

Bayard Rustin: Unsung Crusader for Social Justice

December 31, 2007

Although he was always at the forefront of the civil rights movement, Bayard Rustin’s contributions to the struggle are often overlooked. Perhaps best known as the lead organizer for the 1963 March on Washington that set the stage for Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dreamspeech, Rustin was a ground-breaking theorist and shrewd tactician for the trade-union movement and the fight for racial equality.

“He conceived the coalition of liberal, labor and religious leaders who supported passage of the civil rights and anti-poverty legislation of the 1960s,” notes an AFL-CIO tribute, “and worked closely with the labor movement to ensure African- American workers’ rightful place in the House of Labor.”

Roots of an Activist

Born in West Chester, PA, in 1912, Rustin was deeply influenced by the religious and political beliefs of his grandmother, Julia, a devout Quaker and civil rights activist. As a child, Rustin was exposed to many parlor conversations with frequent guests such as NAACP founder W.E.B. Du Bois.

Rustin’s work as a civil rights activist began while he was in high school in the late 1920s, when he was arrested for refusing to sit in a segregated balcony at a movie theater. Soon he was encouraging classmates to defy “Jim Crow” customs in local restaurants, stores, and at the YMCA near his home.

While establishing a reputation as a dissident, he was his class valedictorian in 1932, and received a prize for public speaking. Rustin attended Wilberforce University (near Dayton, OH), but quit just before finals in his senior year. In 1938, after attending a Quaker-sponsored peace-activist training program at Cheyney State Teachers College, not far from his home town, he moved to Harlem.

While in New York, he became associated with the American Communist Party, then one of the nation’s most outspoken anti-racism organizations. In 1941, however, during the reign of Russian dictator Joseph Stalin, the young pacifist renounced his allegiance, then aligned himself with anti-Communist progressive leaders such as A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car porters, and A.J. Muste of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), an international faith-based peace movement.

Rustin helped Randolph and Muste plan a March on Washington in 1941 to protest segregation in the armed forces, but the leaders agreed to cancel the protest after President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order banning racial discrimination in civilian defense industries. According to one biographer, Rustin vehemently disagreed with the decision to call off the march, siding with those who believed that the higher goal of a color-blind military had not been achieved.

Inspired by Gandhi

Rustin went to work full-time as a FOR organizer, traveling the country to share his ideals with college students and religious and civil rights groups. He and other FOR activists had become inspired by the philosophy and nonviolent social protest methods advocated by Mohandas Gandhi, the leader of India’s struggle to gain independence from British colonial rule.

In 1942, with FOR leaders James Farmer and George Houser, Rustin helped form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which, along with the NAACP, helped lead the civil rights struggle in the decades ahead.

In 1942, with FOR leaders James Farmer and George Houser, Rustin helped form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which, along with the NAACP, helped lead the civil rights struggle in the decades ahead.

CORE activists sought to fuse militant anti-racism with Gandhi’s pacifist philosophy, according to sociologist Stephen Steinberg. The nonviolent sit-ins and boycotts CORE experimented with in the 1940s became a successful “political legacy that was readily adopted by the evolving civil rights movement,” Steinberg wrote.

Rustin’s career was sidelined in 1943 when he was jailed for refusing to enter the draft. As a lifelong Quaker, he was offered — but declined — conscientious-objector status if he performed alternative service to support war efforts.

After serving three years in a federal penitentiary, Rustin went to India for six months. Returning to the U.S. in early 1947, he tried to apply Gandhi’s nonviolent methods in helping FOR and CORE conduct the first “freedom rides” to protest the segregation of interstate bus travel in the South, which had been declared illegal by a 1946 Supreme Court ruling.

He and other activists challenged continuation of the Jim Crow practice by taking seats on buses and trains that, despite the court’s order, were still reserved for whites. They suffered beatings and arrests, and in North Carolina, Rustin was forced to serve 22 days on a chain gang. (The New York Post published Rustin’s report about the experience, and the outrage it produced contributed to the abolition of chain gangs in the state.)

Rustin also was active in the drive to convince President Harry S. Truman to desegregate the armed forces, which he did in 1948. From 1948 to 1952, still working for FOR, Rustin sought to introduce Gandhi-style civil disobedience tactics to independence movements in Ghana and Nigeria. During that time he also formed an organization that supported resistance to apartheid in South Africa.

Soon after his return to the U.S. in 1953, however, the peace activist’s rising star was dimmed following his arrest in California for a private incident involving homosexual activity, which forced him to give up leadership positions in both FOR and CORE. Rustin had never denied he was gay, but amid the reactionary conservatism of the McCarthy Era, many of his colleagues saw his continued leadership in civil rights activities as a public relations liability.

With Dr. King

Despite some leaders’ fears, Rustin continued serving as a behind-the-scenes tactician for civil rights organizations. In December 1955, he was back on the front lines when Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, AL. Her courageous act launched an African-American boycott of the city’s public transportation system and proved a pivotal moment in the nation’s struggle for racial equality.

At A. Philip Randolph’s suggestion, Rustin assisted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in organizing the protest. Despite the obvious dangers, Rustin convinced King and those around him to forgo armed guards and fully embrace nonviolence as the trademark of the modern civil rights movement. King had studied Gandhi, but Steinberg writes that Rustin’s firsthand experience in employing Gandhi’s methods provided the framework for success: “His organizing skills and political savvy proved indispensable,” the sociologist wrote, and outweighed King advisors’ fears that Rustin’s sexual preference and past association with Communists could damage the civil rights movement.

Working largely in the background, Rustin remained a close advisor to King for the next decade, helping organize numerous marches. Rustin also helped King form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and assisted in a draft of King’s first book, Stride Toward Freedom.

Rustin’s Legacy

Though sometimes at odds with militants who feared the movement would be compromised through political accommodation, Rustin spent the rest of his life building coalitions with progressive churches, labor leaders and others who would promote peace and equality.

In 1965, with a grant from the AFL-CIO, Rustin launched the A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI), to forge an interracial coalition that would promote justice and secure jobs for all Americans. Among other initiatives begun under Rustin’s leadership, APRI has fought for better representation of African-Americans in labor unions. Rustin served as APRI’s executive director until 1972.

In 1984, at age 72, Rustin was arrested one final time, for demonstrating in support of clerical workers striking for pay equity at Yale University. He continued to fight for social change at home and abroad until he died, in 1987.Rustin, left, was a key tactician for the August 1963 “March on Washington.”