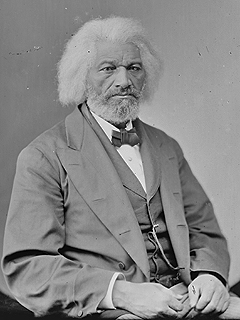

Frederick Douglass: Activist, Orator, Publisher, Statesman

December 31, 2006

(This article was first published in the January-March 2007 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

“If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.” - Frederick Douglass

Unquestionably, the single greatest leap forward in the quest for social and economic justice is the abolition of slavery. In the United States, after decades of struggle and a bloody civil war, slavery was formally abolished in 1865. Today, while we easily recall the contributions of many 20th-Century civil rights leaders, we often ignore a giant from the earliest days of the abolitionist cause: Frederick Douglass.

Unquestionably, the single greatest leap forward in the quest for social and economic justice is the abolition of slavery. In the United States, after decades of struggle and a bloody civil war, slavery was formally abolished in 1865. Today, while we easily recall the contributions of many 20th-Century civil rights leaders, we often ignore a giant from the earliest days of the abolitionist cause: Frederick Douglass.

In one of the most remarkable of all American lives, Frederick Douglass rose from slavery to become one of the 19th Century’s most influential activists for the cause of human rights.

The tragic circumstances of his early life were a common reality for millions of African-Americans in the early 1800s. Born in 1818 on a plantation in Talbot County, MD, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey would have no record of his actual birth date or of his father, who may have been his owner, a white man. Douglass and his mother were separated soon after his birth.

At about age 7, he was sent to work as a “houseboy” in the Baltimore home of Hugh and Sophia Auld. Mrs. Auld grew fond of the precocious child and taught him the alphabet, but her husband forbade any further education. With some help from other boys, however, he taught himself to read and write, becoming fascinated with the power of words. He studied on the sly, and came to regard literacy as the “pathway from slavery to freedom.”

Back to the Plantation

In 1832, the teenager was wrenched from the life of relative ease in Baltimore and sent back to Maryland’s eastern shore to work the fields, where he experienced the bitter realities of life as a plantation slave. The headstrong adolescent was hired out to a “slave breaker,” Edward Covey, who provided him little food or clothing, and worked and beat him mercilessly. After several months of such treatment, Douglass stood up to Covey and fought back.

The lengthy battle with the overseer resulted in a draw, and Douglass could have been hanged for the crime of striking an owner. Fortunately, Covey was not willing to let it be known he had failed to subdue the young man. Douglass was sent to work for a new slave owner. Although he and other slaves were relatively well treated, Douglass was determined to escape to freedom in the North.

The confrontation with Covey “rekindled in my breast the smoldering embers of liberty,” he later wrote. “It brought up my Baltimore dreams, and revived a sense of my own manhood. I was a changed being after that fight. I was nothing before; I was a man now.”

After at least one failed attempt at securing freedom, Douglass escaped to New Bedford, MA in September 1838. He carried false identification papers that showed he was a free man, a seaman. He soon married Anna Murray, a free black woman he had known in Baltimore, and with whom he would have five children. He adopted the surname Douglass to cover his trail as a fugitive slave.

The Abolitionists

Working as a day-laborer, Douglass soon became a respected figure in the New Bedford community and began attending anti-slavery meetings. At an 1841 gathering of prominent white abolitionists in Nantucket, MA, he gave an impassioned speech about his life as a slave. William Lloyd Garrison, a well known journalist, hired Douglass to become a lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

Douglass began to travel widely as a spokesman for the abolitionist cause. With his towering posture, a rich baritone voice, and forceful command of the English language, the orator, only in his 20s, vividly described the horrors of slavery to audiences throughout the free states and in Europe.

To rebut those who doubted that he was a self-educated former slave, he wrote Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Published in 1845, it was to be the first of four editions of his autobiography.

The book was a best-seller, but it exposed him as a fugitive, and he fled to the British Isles after its publication. While abroad, he met with fellow progressives and gained benefactors who purchased his legal freedom in 1846, paying his last owner just over $700 for his “property,” which was roughly the market price of a young male slave.

The Journalist-Orator

Douglass returned to the U.S. in 1847, and settled in Rochester, NY, where he published a series of abolitionist newspapers, including the North Star. He continued to travel throughout the North giving speeches, challenging racist laws in free states, and aiding Underground Railroad efforts. He also embraced other progressive causes of the day, including the fledgling women’s rights movement.

Douglass returned to the U.S. in 1847, and settled in Rochester, NY, where he published a series of abolitionist newspapers, including the North Star. He continued to travel throughout the North giving speeches, challenging racist laws in free states, and aiding Underground Railroad efforts. He also embraced other progressive causes of the day, including the fledgling women’s rights movement.

By the outbreak of the Civil War, Douglass had come to believe that mere “moral suasion” was an insufficient tool for bringing an end to slavery. In speeches and in private meetings with President Lincoln, he focused on making the abolition of slavery a stated Union goal; he also advocated the recruitment of free blacks as troops for the Union army.

Prodded by the rise of radical abolitionist sentiments in the North during the war, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which declared slaves held in Confederate states to be free. Before the war ended in April 1865, Douglass was a forceful voice for congressional passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which banned slavery nationwide. It was ratified by the end of the year.

After nearly 25 years in western New York, Douglass moved to Washington. The most prominent black activist of the time, he worked to help former slaves have a chance to benefit from the promise of equality, helping to secure ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, which mandated due process and equal protection under the law, and gave black men the right to vote. During Reconstruction, Douglass also helped in the passage of the Ku Klux Klan Act and the Enforcement Act, which President Grant, who Douglass supported, used forcefully to protect the rights of newly freed slaves.

With pro-civil rights Republicans controlling the government for several decades following the war, Douglass was appointed to several offices, including police commissioner and recorder of deeds in Washington, and diplomatic posts in Santo Domingo and in Haiti.

Douglass remained a forceful voice for civil rights until he died, at age 77, on Feb. 20, 1895. He was buried in Rochester.