The History of Labor’s ‘Day’

August 31, 2007

(This article was first published in the September/October 2007 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

The celebration of the first Monday in September as a holiday “is a creation of the labor movement and is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers,” according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

In the mid-1890s, Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor, noted that “Labor Day differs in every essential way from the other holidays of the year in any country. All other holidays are in a more or less degree connected with conflicts and battles of man’s prowess over man, of strife and discord for greed and power … Labor Day is devoted to no man, living or dead, to no sect, race, or nation.”

In the mid-1890s, Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor, noted that “Labor Day differs in every essential way from the other holidays of the year in any country. All other holidays are in a more or less degree connected with conflicts and battles of man’s prowess over man, of strife and discord for greed and power … Labor Day is devoted to no man, living or dead, to no sect, race, or nation.”

At that time, the only widely accepted days off for workers — other than Sundays — were Christmas, New Year’s Day, and Thanksgiving. Workers received no pay for those holidays, but with so many willing to take “LWOP,” employers were unable to run their businesses and simply shut down.

Taking the Day Off

In order to make a basic living, the average American worker in the late 19th Century labored 12-hour days, six days a week. Sundays were recognized as a day of rest, but there were no laws limiting the number of hours or days, nor were there incentives for employers to offer time off.

One of the major goals of the organizations that made up the fledgling labor movement was to win a restriction on the hours of work. The first inroads were made by skilled employees who convinced their bosses that getting off early on Saturday would mean a much fresher start the following Monday. (It was the institution of the shorter workday on Saturday that ultimately led to the five-day week, as well as the concept of the weekend.)

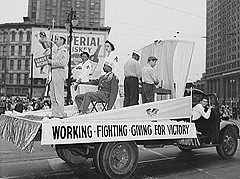

New York City was home to the first Labor Day celebration, on Sept. 5, 1882. Planners wanted to call attention to abusive employer practices, such as child labor, and were seeking laws to promote the idea of a 10-hour workday.

The Central Labor Union (CLU) organized more than 10,000 workers in a march from City Hall, near Wall Street, to Union Square, two miles uptown. The purpose of the parade was to exhibit to the public “the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations.” It was followed by a street festival for the workers — most of whom were on unauthorized leave and risked being fired — and their families.

The parade was a success and a similar event was held the following year. In 1884, the CLU urged labor federations in other cities to join in the “workingman’s holiday” on the first Monday each September. By 1885, “Labor Parades” were being staged in a number of industrial centers across the U.S., and municipal ordinances recognizing the holiday emboldened workers to take part.

State Sanctioned

Although the first bill recognizing the holiday was introduced in New York, the first statewide Labor Day law was passed by the Oregon legislature on Feb. 21, 1887. By the end of the 1880s, nearly 30 states had followed suit.

Although the first bill recognizing the holiday was introduced in New York, the first statewide Labor Day law was passed by the Oregon legislature on Feb. 21, 1887. By the end of the 1880s, nearly 30 states had followed suit.

Many of the celebrations featured speeches and demonstrations calling for a “national” holiday, with these calls for federal recognition becoming more vocal each year. But it took a labor debacle to prompt the establishment of a federal day in labor’s honor.

The American Railway Union, a single organization that represented all crafts of railroad employees, was formed in March 1893. That August, the Chicago-based Great Northern Railroad made the first of three rounds of wage cuts. After the third pay cut, in March 1894, ARU members voted to strike, and shut down the rail line for 18 days, until wages were restored.

Thousand of railway workers soon had joined the ARU, including a large number of Pullman Palace Car manufacturing employees. In May 1894, after wage cuts at the Chicago plant, the Pullman local went on strike and the ARU voted to refuse to work any trains that included the company’s cars.

The railroad companies responded by attaching Pullman cars to U.S. Mail trains. Once the boycott was shown to be delaying the mail, a court ordered ARU members back to work. When the judicial directive was ignored, President Grover Cleveland sent in federal troops and famously said: “If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered.”

After nearly two months of sporadic incidents of arson and looting, while soldiers helped move the mail, the strike collapsed. In the aftermath, labor leaders were sent to prison, the railway union was disbanded, and Pullman employees were forced to pledge that they never again would unionize. Despite the disastrous outcome of the strike, Cleveland was prevailed upon to sign a “Labor Day” bill that Congress had approved at the height of the unrest.

The bill was worded to honor the original Labor Day parade of 1882 and was set for the first Monday in September. But the selection of September for the observance of Labor Day may have had more to do with a desire to avoid having it coincide with May Day.

That Day in May

In some places, May Day is a light-hearted celebration of spring. But in many countries, “International Workers Day” is a national holiday originally associated with political protests and street rallies. Although some were organized by workers and their trade unions, anarchists and socialists often played a strong role.

It was at a gathering of socialists in Paris in 1889 that May Day was established, as a commemoration of the “Haymarket” incident in Chicago in early May of 1886. Four strikers had been killed at a manufacturing plant following a citywide protest in support of the eight-hour day, and a rally at Haymarket Square was planned to honor the victims. Organized largely by anarchists, it culminated in an explosion that killed a policeman and led to a riot during which at least a dozen police officers and demonstrators were killed by gunfire.

In communist countries such as the People’s Republic of China, Cuba, and offshoots of the former Soviet Union, May Day is purportedly a salute to workers. But it typically is overshadowed by elaborate military parades.

Out of the Depression

Out of the Depression

In the U.S., the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 is considered the “main pay law of the land,” because it regulates minimum wage and overtime pay at the federal level. But the FLSA does not require holiday pay or time-off. However, with all levels of government routinely closing public offices on “legal holidays,” public-sector employees began to receive full wages for the time off. And many private-sector employers began to follow a tradition of paying their employees for those same days. Yet even today there is no law that requires private-sector employers to give their workers a day’s pay for staying home on a federal holiday.

There is, however, a day to honor the efforts of those who worked toward to create holidays, as well as all other types of paid leave. And though Labor Day is meant as a celebration of the labor movement and its many achievements, the “holiday” that set the pattern for all three-day weekends to follow is now celebrated mainly as a long work-break that officially closes out the summer.