Looking Back on Labor History: Postal Banking, Operation Dixie, & the Eight-Hour Work Day

June 7, 2023

(This article first appeared in the May/June 2023 issue of The American Postal Worker)

Postal Banking: Congress Established Postal Savings System

On June 25, 1910 Congress established the Postal Savings System, which offered fully-guaranteed deposit accounts to all. The program was especially helpful to lowincome households who could not secure bank accounts, and to communities without local bank branches.

On June 25, 1910 Congress established the Postal Savings System, which offered fully-guaranteed deposit accounts to all. The program was especially helpful to lowincome households who could not secure bank accounts, and to communities without local bank branches.

By 1929 the Post Office held $153 million in savings deposits and $1.2 billion by the 1930s. Postal savings peaked in 1947, with $3.4 billion in holdings for more than four million people in over 8,000 Post Offices.

The Postal Savings System highlighted the need for financial services in every community and the Post Office's ability to meet that need.

After World War II, a growing commercial banking industry began lobbying against the Postal Savings System. That pressure, together with higher commercial interest rates, and the advent of federal bank deposit insurance led to Congress ending the Postal Savings System in 1966, leaving many towns and communities without a financial institution.

“Postal banking was America’s most successful experiment in financial inclusion – a problem we face again today,” wrote professor Mehrsa Baradaran, a scholar of banking law, financial inclusion, inequality, and the racial wealth gap.

For more information on the Campaign for Postal Banking, visit: www.campaignforpostalbanking.org.

Congress of Industrial Organizations Launched "Operation Dixie" in Divided South

May 1946 – The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) union federation launched a southern unionization campaign dubbed “Operation Dixie.” It was called “the most important drive of its kind undertaken by any labor union in the history of this country” by CIO president, Philip Murray. In the wake of the Great Depression and World War II, many business owners moved production from the industrial North to the racially-segregated South to take advantage of lower wages and lower unionization rates. To counter this attack on workers, the CIO recruited 250 organizers to build union power in the South.

In 1946, Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers, Local 22, led by CIO organizer Philip Koritz, recruited black and white members into a desegregated union. After an unprecedented and extraordinary organizing drive, the local went on the offensive against the Piedmont Leaf Tobacco Plant, submitted a list of demands, and went on strike.

Workers faced stiff opposition from local authorities, including from the Winston-Salem Police Department, which arrested striking workers and Koritz, who was sentenced to a year of imprisonment in a forced labor camp and was then exiled from North Carolina. The strike lasted from July until September, when workers secured many of their demands, including a 60-cent minimum wage and three paid holidays.

However, despite successes such as the Piedmont Leaf Tobacco Plant strike, bosses successfully fought back against Operation Dixie. By exploiting deep-rooted racism, Jim Crow laws, harassment from the Ku Klux Klan, violently hostile local authorities, the passing of anti-union right-to-work laws in 1947, and growing Cold War hostility to unions, the growing wave of unions in the South was stalled.

Operation Dixie officially ended in 1953, but the fight to end racial division and organize workers in the South and across the country continues to this day.

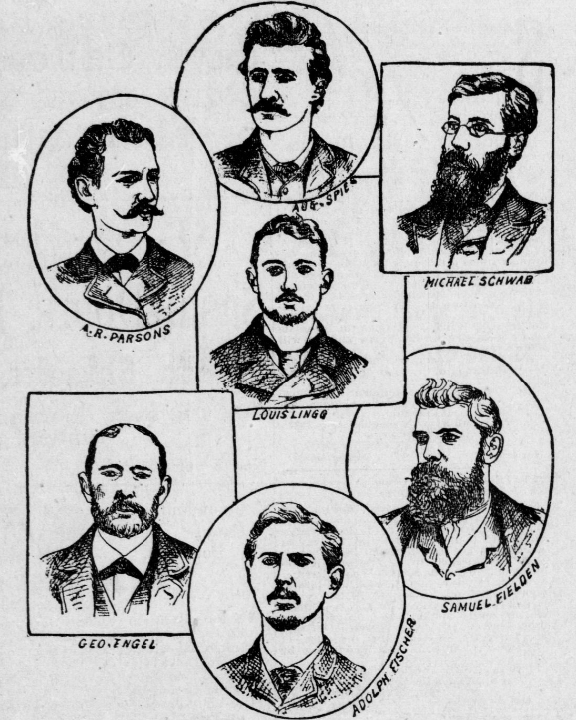

Chicago Haymarker Affair and the National Struggle for an Eight-Hour Work-day

May 4, 1886 – The “Haymarket Affair” in Chicago capped off a week of protest for workers, who had taken to the streets in a national campaign to secure an eight-hour workday.

On May 1, 1886 more than 340,000 workers took part in national actions in support for an eight-hour day. In Chicago, 80,000 protesters peacefully marched through the streets, singing their demand.

Two days later, activists organized a union action at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, where scabs had replaced lockedout workers on strike. Police arrived to intimidate the strikers, under the guise of protecting the scabs, beating strikers with billy clubs. As protestors exited, police ran at them and fired into the retreating crowd, killing at least six and injuring many more.

The following day, labor leaders organized a rally in Haymarket Square. While the event was meant to be a non-violent protest of police brutality, a reporter told organizers, Albert Parsons and August Spies, “We hear there’s going to be some trouble tonight.” More than 180 police officers had mobilized under the command of Captain John “Clubber” Bonfield.

The mayor, who saw that the rally was calm and beginning to disperse, told Bonfield and his men to stand down. Instead, police rushed the podium, and beat protestors with clubs.

At this point, an unidentified individual threw a bomb, killing one police officer and wounding another. Police opened fire on the crowd, killing several civilians and fellow officers, and injuring several dozen more.

While the identity of the bombthrower is not known, many believe the organizers were set up. Within days Parsons, Spies, and six others were indicted for the murder of an officer.

The trial was a sham, with a jury that was comprised of businessmen, their clerks, and a relative of a man killed. Testimonies were full of contradictions and witnesses were paid to testify.

Seven defendants were sentenced to death. Of the group on trial, only Parsons and Spies were on-scene when the explosion occurred. They were in plain sight on the podium at the time.

“If you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement... then hang us!” Spies told the judge.

“Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you and in front of you and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.”

News of the tragedy sent shockwaves through the labor movement worldwide. In 1889, labor advocates declared May 1 International Workers Day – or May Day – to commemorate the struggle of the Haymarket Affair and to build international workers’ solidarity.

Canadian Postal Workers Secure Paid Maternity Leave After 42-Day Strike

June 29, 1981 –Twenty-three thousand workers from The Canadian Union of Postal Workers led by President Jean-Claude Parrot, launched a victorious 42-day strike for paid maternity leave. The CUPW was the first federal union in Canada to win 17 weeks of paid maternity leave, and they did so at a rate of 93 percent of full wages.

“Women deserve full economic protection for the short time they leave the work force to recuperate from childbearing and to establish a relationship with the newborn child,” wrote Dr. Gail Hutchinson, president of the London (Ontario) National Acton Committee on the Status of Women, in a letter to the editor of The London Free Press.