Mother Jones

February 28, 2005

(This "Look Back" feature first appeared in the March/April 2005 issue of The American Postal Work Magazine.)

Although vilified by her detractors as “the most dangerous woman in America,” struggling workers all over the nation had a more affectionate way of referring to Mary Harris Jones: They called her “Mother.”

From 1871 to 1924, Mother Jones traveled far and wide to fight for decent wages and better working conditions, spreading the union gospel to those who needed it most. A frequent visitor to in worker camps, shantytowns, tenements, union halls, and jails, the diminutive Mother Jones was nonetheless a charismatic figure and a powerful if, at times, salty-tongued, orator.

“She had force, she had wit, above all she had the fire of indignation,” said Upton Sinclair, the Progressive Era novelist whose most famous work, The Jungle, was an indictment of Chicago packinghouse conditions. “She was the walking wrath of God.”

“All over the country she had roamed, and wherever she went, the flame of protest had leaped up,” Sinclair wrote. “Her story was a veritable Odyssey of revolt.”

Hard Life Forges Commitment

Born in Ireland in 1830, Mary Harris as a child experienced firsthand the brutal reality of poverty at the dawning of the Industrial Revolution. Her grandfather was hanged for rebelling against his British landlords, and when her father faced the same fate, the Harris family fled to North America. They settled in Toronto, where her father found work in construction. Mary studied to be a teacher and worked at a Michigan Catholic school before moving to Chicago in the late 1840s. She worked as a dressmaker and then a few years later moved to Memphis, where she resumed her teaching career. At the age of 31, she married George Jones, an iron molder and union leader.

The Joneses had four children in six years. In 1867, Mother Jones lost her entire family to a yellow fever epidemic. Alone and with few choices, she returned to Chicago , and opened a dressmaking shop. According to one biographer, the store catered to the wealthy, and she became increasingly distressed by the disparity between the living conditions of the “lords and barons” for whom she worked, and the “poor, shivering wretches, jobless and hungry” she saw all around her. “My employers seemed to neither notice nor to care,” she said.

In 1871, tragedy struck again when Jones lost her store and everything else she owned in the Great Chicago Fire. Lost to history is much of Jones’ life from age 40 to age 64. It is known that she became involved with the Knights of Labor, the largest workers’ organization in the world at the time, and that she began to dedicate all her energies to the fledgling American labor movement.

Tender, but Tough

As the nation moved from an agricultural to an industrial economy, waves of displaced farmers and new immigrants worked long hours for starvation wages, often in dangerous conditions.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Jones reportedly was involved in various union and political causes in Denver, San Francisco, Chicago and Pittsburgh. She apparently had no steady income or address. When asked where she lived, she would respond, “wherever there is a fight.”

It was also during this period that she became known as “Mother Jones,” apparently for her gentle ability to lift the hearts of the downtrodden, whom she adopted as family. Still, she was known for her toughness: It was said that she “could cuss the chickens off the roost and step over a snake without blinking an eye.”

Though a legend among those who had seen her in action, Jones was relatively unknown until she was well into her sixties. In 1894, she gained national attention for her role in organizing a march on Washington on behalf of unemployed Colorado workers, and for her well-publicized aid to black and white miners during an Alabama coal strike. In 1896, she helped stage a large rally in support of Eugene V. Debs, the jailed leader of a major rail workers’ strike and later the five-time Socialist candidate for U.S. President.

In 1897, after leading mobilization and support for 20,000 Pennsylvania miners during a national coal strike, Jones was hired by the United Mine Workers as an organizer. She worked on and off for the UMW for nearly 25 years. “In the miners’ cause,” a historian wrote, “she waded creeks, faced machine guns, and taunted many a mine guard to shoot an old woman if he dared.”

Sometimes clashing with the UMW’s leadership, Mother Jones would leave the organization to help workers organize in other industries, and to dabble in various progressive political causes. Particularly dear to her was the issue of child labor.

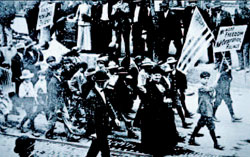

In 1903, Jones organized her famous “March of the Mill Children” from eastern Pennsylvania to President Theodore Roosevelt’s summer home on Long Island. “Every day, she and a few dozen children — boys and girls, some 12 and 14 years old, some crippled by the machinery of the textile mills — walked to a new town,” wrote a recent biographer, “and at night they staged rallies with music, skits, and speeches, drawing thousands.”

Roosevelt refused to meet with Jones and her charges, but the march prompted at least the Pennsylvania legislature to enact tighter employment restrictions and gave momentum to the movement to end child labor.

More Causes

In 1904, Mother Jones lectured throughout the Southwest for the Socialist Party of America. The following year, she was the only woman among the 27 founders of the International Workers of the World (the Wobblies). By 1911, she had also worked with Milwaukee brewery workers, Chicago telegraphers, southern textile workers, New York City garment workers, and exiled Mexican revolutionaries.

At the age of 81, Mother Jones was back on the UMW payroll, but she continued to chart her own path. She spent much of her time in West Virginia, where conditions among miners’ families were consistently among the worst. Virtually everyone lived in a company-owned shack and worked not just in dangerous underground shafts, but for seven days a week. Pay was in “scrip,” which was redeemable only at mine-owned stores.

Miners who dared to protest or get involved in union activity were routinely threatened or blacklisted. Organizers were run out of town, beaten, and even murdered by coal-company thugs.

Jones proved fearless, and had a knack for gaining publicity. During the violent Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912-1913, Jones led a march of miners’ children through the streets of Charleston, the state capital.

The national publicity was more than the mine owners could stand: In early 1913, the 83-year old Jones was arrested, tried, and convicted of conspiracy in the murder of a company guard. Her imprisonment created such a furor that the U.S. Senate began an investigation and the newly elected West Virginia governor, Henry D. Hatfield, set Jones free.

Later in 1913, Jones again was jailed for assisting coal miners, this time in Colorado, where she played a role in a number of protracted strikes. In April 1914, in Ludlow, CO, 20 people — including a dozen women and children — living in a miners’ tent colony were massacred by state militiamen and coal company operatives. Jones swung into action, venting her outrage in cities across the country, prompting President Wilson to propose the creation of a grievance committee at every mine.

After another decade of roaming the country to preach the union gospel, Mother Jones “retired” from the UMW at age 93, settling in the home of her friend, Knights of Labor leader Terence Powderly, near Washington, DC. She continued to speak out, hitting the road for the last time in 1924 to appear at a rally for striking dressmakers in Chicago, where her life as an activist was forged.

Mother Jones died at the Powderlys’ home on Nov. 30, 1930 , seven months after her 100th birthday. At her request, she was buried in the Union Miners’ Cemetery in Mount Olive, IL.

(Photos courtesy of the United Mineworkers of America)