The Post Office Department and Jim Crow

December 31, 2005

(This article was first published in the January/February 2006 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Editor’s Note: In a letter to The American Postal Worker, an APWU member noted that our “Look Back” article on the Railway Mail Service (September/ October 2005) did not discuss workplace discrimination. We felt that the reader raised an issue that deserves a closer look.

Although slavery had been outlawed, there were virtually no laws or regulations after the Civil War that provided African-Americans with protection against racial discrimination on the job, unless they worked for the federal government.

In 1883, as part of a reform movement to root out corruption and political cronyism, Congress created a civil service system that based federal work rules on merit. The rules, at least in theory, were supposed to be colorblind.

But in 1893, southern Democrats, emboldened by the Supreme Court “separate but equal” decision that that legalized state-sanctioned racial discrimination, began to enact and enforce “Jim Crow” laws. African-Americans faced legalized color barriers in every facet of life, from being denied access to public facilities to being denied justice in the courts.

The federal government, on the other hand, remained largely under the control of liberal northern Republicans, many of whom sought equal opportunity for all. Despite the rise of Jim Crow, the merit system remained in place and the federal government became the nation’s largest single employer of African-Americans, most of whom worked for either the Treasury or the Post Office. In addition to manual laborers, clerks, and auditors, there were black postmasters and an assistant attorney general.

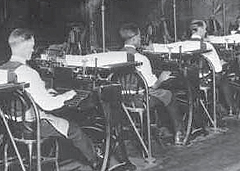

“The practice of using merit testing in filling federal job vacancies had largely erased the color line,” said historian Nicholas Patler in his 2004 study, Jim Crow and the Wilson Administration. He described the work environment for African-Americans as “relatively integrated” for decades, “even in most Railway Mail Service runs in the South, and both races worked together at many post offices in large southern cities, including Montgomery, Mobile, Houston, and Jacksonville.”

Woodrow Wilson and Jim Crow

The relative equality that black federal employees enjoyed for several decades was undermined, however, by President Woodrow Wilson. As a candidate, the born-and-bred southerner had promised black Americans “absolute fair dealing.” But the first chief executive from the South in more than 50 years soon turned his back on his black supporters.

“Wilson’s electoral landslide in 1912 brought the South back into the national political orbit for the first time since the Civil War,” said Washington and Lee University historian Ted DeLaney. “Once in office, these southerners responded to many of the wishes of white supremacist groups.”

One such hate group was the National Democratic Fair Play Association. Soon after Wilson took office, the group wrote to Albert S. Burleson, the newly appointed postmaster general, and demanded segregation in the Railway Mail Service.

Burleson, a former Texas congressman, was sympathetic and he announced in an April 11, 1913, cabinet meeting that segregation of postal railway work would take place gradually, and that African-Americans would remain employed by the Post Office only where such “would not be objectionable.”

While there had always been some discrimination, “The changes made by the Wilson administration were unparalleled,” DeLaney wrote. “Cabinet members moved quickly to segregate black workers or to purge them from the federal civil service.” A recent study by the Labor Department notes that upon taking office, “Burleson immediately set out on a program to segregate, downgrade and, in some cases, discharge Negro workers… [He] also ordered segregated window service to the public.”

No official government records have been found that indicate how many black postal workers were driven from their jobs. The discrimination policies did, indeed, go into effect gradually, and were likely conveyed by word of mouth, largely by Burleson-appointed postmasters. Patler’s study revealed “an intensely clear pattern to segregate, reclassify, and discharge African-American workers.”

Systematic Bias

One way that the Wilson administration got around the merit system rules was by requiring, beginning in May 1914, that job applicants submit photos to accompany the results of their civil service exams.

The previous year, the National Postal Alliance was formed by black workers who had suffered on-the-job discrimination and also had been excluded from postal unions. According to the Alliance’s official history (published in 1956), “The system aided and abetted many appointing officials ... Reports of successful Negro applicants being certified three times and [not hired], and the fact that practically no [black] appointments were being made to the Railway Mail Service ... caused our belief that the photo was a chief or contributing reason.”

African-Americans found themselves “harassed on outrageously trumped-up charges, and endured repeated racial slurs and racial humiliations,” Patler wrote. The historian said that it is clear that the Post Office Department enforced Jim Crow not only in the South, but at its Washington headquarters and in many railway mail routes.

Fighting Back

The discrimination campaign received strong opposition from the Alliance (today known as the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees) and the newly formed NAACP. W.E.B. Dubois and other civil rights leaders, drawing on reports of discrimination gathered by black workers, confronted the Wilson administration with data and personal accounts suggesting trends throughout the federal government that undermined the merit system and his promise of “fair dealing.”

Wilson was surprised by the volume of criticism he received in the form of letters, petitions, and newspaper editorials from every state. Protest meetings drew crowds comparable to those during the civil rights movement in the 1960s and are credited with stemming the spread of segregation in government employment. “It took a hard fight with letters, interviews, and publicity to secure even a mild breaking down,” Dubois recalled of the multi-pronged discrimination campaign of the Wilson era.

By the eve of the U.S. entry into World War I a few years later, “a new demand for labor had come,” Dubois later wrote.“Migration of Negroes to Northern centers of industry was increasing and a wave of war-born economic prosperity was sweeping over the country and over black folk.”

After Wilson

Although the war effort meant increased work for everyone, discrimination had become the norm in federal work, and as Patler notes, for many years, African Americans were relegated to “the lowest paying work.”

Civil rights leaders continued pressing for an end to discrimination. In late 1940, as the U.S. prepared for war, they succeeded in pressuring Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to end the photograph requirement. Less than a year later, FDR, faced with A. Philip Randolph’s threat of a massive protest march on the nation’s capital, issued an executive order banning “discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin” in the federal government and in defense industries. “With the stroke of a pen,” Patler wrote, “the New Deal president disrupted the almost thirty-year-old pattern of federal Jim Crow that had been established during the Wilson years.”

Historical references tend to credit Postmaster General Burleson with the creation of Air Mail, Parcel Post, and with improvements in rural delivery. Unfortunately, his racist legacy has been largely overlooked, as well as his efforts to cut postal pay, lengthen the work week, ban postal strikes, and censor mail during World War I. Fortunately, despite Burleson’s efforts, the Post Office established a reputation for providing relatively equal employment opportunities, especially in comparison with other large employers.