The Real Norma Rae

August 31, 2014

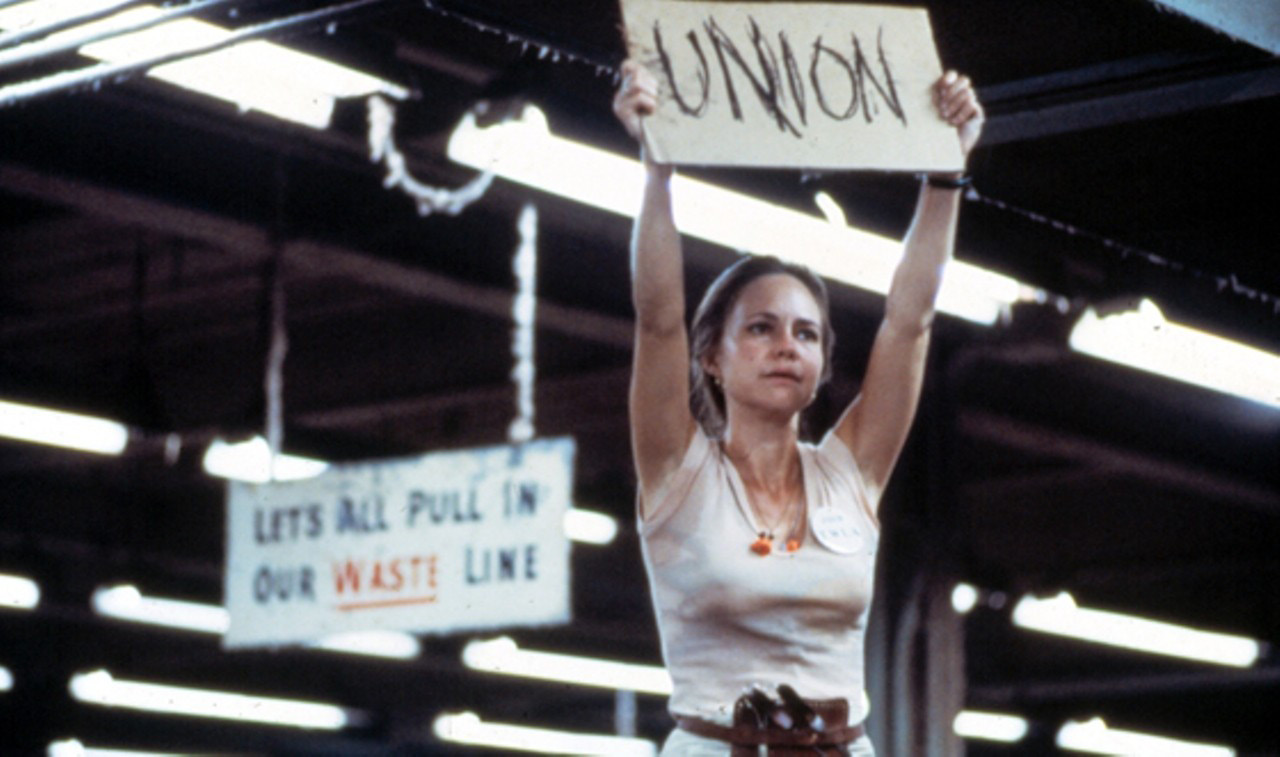

Early On May 30, 1973, the J.P. Stevens textile mill in Roanoke Rapids, NC, fired 32-year-old Crystal Lee Sutton. Before Sutton left the plant, she climbed atop a table on the shop floor and raised above her head a piece of cardboard with the word “UNION” scrawled on it, turning slowly in a circle so that all of her co-workers could read the sign.

Early On May 30, 1973, the J.P. Stevens textile mill in Roanoke Rapids, NC, fired 32-year-old Crystal Lee Sutton. Before Sutton left the plant, she climbed atop a table on the shop floor and raised above her head a piece of cardboard with the word “UNION” scrawled on it, turning slowly in a circle so that all of her co-workers could read the sign.

If this story sounds familiar, that’s because it was the basis for the most memorable moment of the Academy Award winning 1979 movie, Norma Rae. Based loosely on Henry Leifermann’s 1975 biography of Sutton, Crystal Lee, A Woman of Inheritance, the movie was a fictionalized account of the textile workers union’s campaign to unionize the J.P. Stevens textile mills.

For decades, J.P. Stevens called the shots in Roanoke Rapids, paying poverty wages and offering deplorably unsafe working conditions. Workers routinely lost fingers, inhaled cotton dust, and lost their hearing due to the deafening clatter of machinery. J.P. Stevens was so vehemently anti-union that it systematically purchased small unionized textile mills throughout the south just to close them down. But as determined as J.P. Stevens was to keep its workers down, Crystal Lee Sutton was even more determined to lift them up and bring in a union.

From Shop Floor to Front Porches

While at work in mid-April 1973, Sutton saw a flier announcing a union organizing meeting. She had no previous association with unions, nor did she have any prior experience with collective resistance, but she had long harbored resentment towards J.P. Stevens for the power the company held over mill families in Roanoke Rapids.

As the daughter of mill workers herself, Sutton felt mill workers’ children learned an attitude of resignation from their parents. “All their life, all the children ever hear is J.P. The parents come home and say, ‘Lord a mercy, they worked me down today,’” she explained to Leifermann.

At the first union meeting she attended with her friend Liz Johnson in a small African-American church, Sutton was one of only a handful of white workers. Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) lead organizer Eli Zivkovich noticed the two white women in the front row immediately. As he wrote in his first weekly report to his supervisors in Charlotte, the “major problem was lack of white interest.” He encouraged Sutton to come to more meetings and explained that it was “imperative to get the white people involved here.”

Sutton’s presence at meetings and in the mill, wearing the biggest union pin Zivkovich had, was no doubt a boon to the campaign, which suffered not only from a lack of white support but also from the company’s intimidation of all workers, black and white, who showed any interest in or support of the union.

In the early years of the campaign, a great deal of union activity occurred in the kitchens and on the front porches of mill workers’ homes. “House-calling” was – and still is – a common tactic employed by organizers to foster familiarity and friendliness, but also to provide a private space where workers could escape company surveillance.

Hosting meetings at home also helped Sutton balance her responsibilities as a mother with her union activism, as many women were compelled to do. Beverly Riggs, an employee at Stevens’ fabricating plant in Roanoke Rapids, at first stayed home with the children while her husband Rylan attended union meetings. Dissatisfied with receiving information secondhand, Riggs explained, “I started going to union meetings too, and we just carried the children with us. After that, I got more involved with the union than Rylan.” Literally bringing the union home with her, Sutton hoped to teach her children that they should stand up for themselves.

Confrontation at Delta #4

J.P. Stevens mounted one of the most hostile union-busting efforts in history, amassing over 122 unfair labor practice rulings.

J.P. Stevens mounted one of the most hostile union-busting efforts in history, amassing over 122 unfair labor practice rulings.

Around the end of May, management posted a four-page letter addressed to the mill workers on the company bulletin board. In addition to anti-union rhetoric, the letter implied that the union was a front for a black power movement that would take over the plant and the town.

The bosses at Stevens knew that the union could bring charges against them before the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) for posting a racially inflammatory message on company property. When Sutton tried to copy the letter on May 28, Assistant Overseer Dave Moody stopped her.

But Sutton could not be deterred. At first, she considered copying the letter discretely to avoid a confrontation. She enlisted the help of a co-worker, and together they plotted to memorize the letter paragraph by paragraph and sneak off to the ladies’ room to write down the pieces. This tactic, however, proved ineffective. It was taking too long, the women would forget the precise wording, and their frequent trips to the bathroom drew the attention of bosses.

A few days later, as her co-workers filed into the cafeteria for their dinner break, Sutton took advantage of a moment when attention was diverted away from the bulletin board to copy the letter. Moody and General Overseer James Alston saw her and objected, but Sutton insisted that she had the right to copy the letter during her break. When General Supervisor Mason Lee ordered her to stop, she replied, “Well, Mr. Lee, I didn’t know you knew my name,” and continued to copy. When he threatened to call the police, she laughed and said, smiling at him, “Mr. Lee, I am going to finish copying this letter. And then, I am going to eat … supper.”

Sutton copied the letter word for word in front of them. When she finished, she tucked the paper inside her shirt, certain that “nobody will get it down there.”

After supper Moody directed her to Mason Lee’s office. In Sutton’s account, Lee never mentioned the letter. He berated her for using the pay phone on company time. Sutton refused to respond to his accusations. Lee shouted at her to leave the plant.

Uncertain what to do next, Sutton insisted that she return to her workstation to retrieve her purse. The men offered no objections and she stormed back to the shop floor. Her supervisors followed her, joined by a security guard and a police officer. “Out of sheer frustration,” Sutton scrawled one word, UNION, on a piece of cardboard. She climbed up on to her workstation and held the sign above her head. As she turned slowly in a circle, workers began shutting down their machines and raising their hands in the “victory” sign. Mabry ordered her to come down, but no one laid a hand on her.

Although she was fired and arrested, Sutton helped workers at J.P Stevens win the right to be represented by the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) in 1974. In 1977, she was awarded back wages and her job was reinstated by court order. Because she had moved out of the area she chose to return to work for just two days.

Crystal Lee Sutton was a hero in our lifetime who inspired workers the world over. Throughout the remainder of her life she continued to be an outspoken advocate for unions and working people. Following a long battle with cancer, Sutton died on Sept. 12, 2009, at the age of 68.