Remembering Postal Heroes 10 Years Later

October 31, 2011

Just weeks after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, with the country still wracked with fear and anger, we learned of another deadly threat: Anthrax was being sent through the mail. Despite the dangers, postal workers kept the mail moving, as the nation confronted a new and unknown menace.

Deadly Letters

In early October 2001, several incidents of anthrax poisoning were reported, but it was not known how the victims had become infected. An employee of American Media in Boca Raton, FL, and the infant son of an ABC news worker in New York City had died from the disease, and several employees of NBC and CBS in New York had become severely ill.

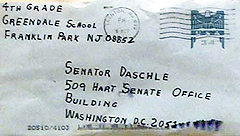

When a threatening letter sent to Senate Majority Leader Thomas A. Daschle (D-SD) was found to contain anthrax, it became clear that the deadly pathogen was being disbursed through the mail.

No one knew how widespread the attacks were, but APWU members refused to panic. “We will not be cowed by those who wish to instill terror,” then-President Moe Biller said, “and we will come through this together.”

The union leapt into action, and insisted that everything possible must be done to ensure workers’ safety. Despite assurances from the USPS and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) that there was little risk of contracting anthrax from mail, the APWU and other postal unions began meeting daily with the Postmaster General and federal health officials to devise methods to protect workers and the public.

Among other protective measures, the union reported on Friday, Oct. 19, that:

- Any facility found to be contaminated would be closed immediately;

- Free anthrax tests would be provided to any employee who may have come in contact with contaminated mail;

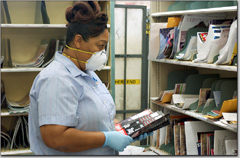

- Upon request, protective gloves and masks would be provided to any employee who handled the mail;

- Mail processing workers would be allowed to wash their hands every two hours; and

- The USPS would begin irradiating mail at key facilities.

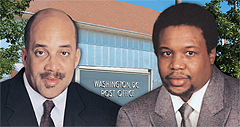

That weekend, the worst fears of postal workers were realized: APWU members Thomas L. Morris Jr. and Joseph P. Curseen Jr. became severely ill and died.

The Victims

Morris and Curseen operated mail processing equipment at the Brentwood facility in Washington, DC. A third worker at the facility, Leroy Richmond, nearly lost his life as well.

Morris and Curseen operated mail processing equipment at the Brentwood facility in Washington, DC. A third worker at the facility, Leroy Richmond, nearly lost his life as well.

Anthrax-laden letters to lawmakers in Washington, NBC News in New York City, and the New York Post had been processed at the Trenton Processing and Distribution Center in Hamilton, NJ, and Trenton Clerks Norma J. Wallace, Jyotsna Patel, Patrick O’Donnell; Maintenance Mechanic Chris Morgano, and Letter Carrier Terry Heller contracted cutaneous or “skin” anthrax poisoning. Although they were severely sickened, their illnesses were not life-threatening.

Safety experts recommended that those who suspected they had been exposed to anthrax take the drugs ciproflaxin or doxycycline. Many who opted to take the medicines reported adverse effects, such as lightheadedness, stomach problems, rashes, or joint pain, and the union called on Congress to authorize a long-term study of the effects of the medicine.

In all, 22 cases of anthrax-related illnesses were attributed to contaminated letters, affecting postal workers, media personnel, congressional staffers, and a 94-year-old old Connecticut woman, who died after contracting anthrax from mail processed at the Southern Connecticut P&DC.

Fork in the Road

The deaths of Morris and Curseen demonstrated that the danger to postal workers was extreme, notwithstanding the reassurances of the USPS and CDC. “Despite our commitment to serving the public,” newly-elected APWU President William Burrus said in November 2001, “we should not be expected to put our lives at risk in a facility that is known to be contaminated.”

The deaths of Morris and Curseen demonstrated that the danger to postal workers was extreme, notwithstanding the reassurances of the USPS and CDC. “Despite our commitment to serving the public,” newly-elected APWU President William Burrus said in November 2001, “we should not be expected to put our lives at risk in a facility that is known to be contaminated.”

Workers at the Brentwood plant were outraged that their facility had not been closed immediately after it was determined that the letters sent to Sen. Daschle and others on Capitol Hill had been processed there.

“We felt our employer took our lives for granted,” recalled Dena Briscoe, current President of the Nation's Capital Southern MD Area Local.

“Management shouldn’t have waited for CDC to order the plant closed,” she added. “When the plant was being tested, we saw outside officials walking around in biohazard suits, and wondered why we were allowed to be in the building with no protection.

“Now, 10 years later, we’re still trying to heal and move forward from that traumatic experience.”

Haunted by the deaths of their co-workers and the belief that their safety had been needlessly jeopardized, they formed a support group, Brentwood Exposed. The group offered emotional support and education, spoke out on behalf of the employees, and initiated a lawsuit. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed.

Early on, the USPS decided unilaterally that closures would take place on a case-by-case basis with input from the CDC and local health officials, leaving the union with little say in the verdict.

The APWU helped ensure that the Brentwood and Hamilton facilities were closed for thorough decontamination, but the USPS kept the Wallingford, CT plant open after mail processing machinery was decontaminated because it claimed that testing in December 2001 found only trace evidence of anthrax. In early spring 2002, however, the New York Times reported that a Connecticut Health Department scientist said he had seen a report indicating that the plant remained contaminated.

For months, the union had been working collaboratively with the USPS to keep the mail moving and to protect workers and the public, but employees who continued working at the Wallingford plant felt betrayed by postal management’s failure to disclose critical safety information.

Almost overnight, workers there “went from being very proud, patriotic postal workers to being very, very angry,” said APWU Northeast Region Coordinator John Dirzius, who was president of the Greater Connecticut Area Local at the time. At a plant meeting, one worker excoriated managers for downplaying the anthrax risk after the initial post-clean-up testing, Dirzius recalled. “You put my family at risk,” she said. “You made a decision for me that I should have been able to make.”

The union got the plant closed immediately for retesting. Workers were granted paid leave for several days, then reassigned to other facilities for several weeks while the plant was more thoroughly decontaminated.

The Brentwood and Hamilton facilities remained closed for many months while they were decontaminated and refurbished. Brentwood reopened in December 2003, but the Hamilton facility was not reopened until March 2005.

“Those were scary times for all of us, but we stuck together and that’s what really brought us out of this,” Trenton Metropolitan Area Local President Bill Lewis recalled at an Oct. 18 ceremony marking the 10-year anniversary of the attacks at the Hamilton facility, “because we stayed united and we fought everything that got in our way and that’s why we’re here today.”

Honoring Postal Victims

Following the attacks, postal workers were widely praised for their bravery. On Nov. 14, 2001, Congress passed a resolution declaring that “the men and women of the United States Postal Service have done an outstanding job of collecting, processing, sorting and delivering the mail during the time of national emergency."

The APWU dedicated its 2002 biennial convention to the victims and all the workers who kept the mail moving despite the dangers. Postal victims and their family members were invited to attend the ceremonies. “We have received so much love and attention from postal employees and the union,” said Mary Morris, widow of Thomas L. Morris Jr., “that we know our husbands did not die in vain.”

Shortly after the convention, Congress unanimously passed a resolution to rename the Brentwood facility in honor of Morris and Curseen.

Aftermath

In June 2012, Congress passed the Public Health Security and Bio-Terrorism Response Act, which included a provision advocated by the AWPU that directs the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) to conduct research on ways to protect workers from future attacks, and on the long-term health effects of ciproflaxin and doxycycline.

The House and Senate also held several hearings at which APWU officers testified about the union’s struggles to ensure that workers were given timely and accurate information about the risks they faced.

The USPS has added biohazard detection equipment at key points in the mail stream, and career postal workers are well-versed in the protocols for handling suspicious mail. And if a widespread attack were to happen in the future, the USPS would help distribute life-saving drugs to citizens.

“Ten years ago, postal workers were hailed as heroes,” noted APWU President Cliff Guffey. “Today, we’re still patriots. We’re still on the front lines.”

Attacks Still Unsolved

After years of investigation, the FBI was unable to prove that either of two American scientists who had conducted research on anthrax for the army was responsible for the attacks. Dr. Steven J. Hatfill, named as “a person of interest” by the FBI in 2002, was exonerated in 2008 and awarded a sizable financial settlement. A second suspect, Dr. Bruce E. Ivins, committed suicide in July 2008 after learning he would likely be charged with the crimes. He was said to have suffered from mental illness. The Justice Department closed the case in 2010, asserting that the evidence against him was overwhelming, but questions remain.