Rev. James Orange: A Champion for Labor and Human Rights

December 31, 2010

“An Alabama sheriff in Marion once told a young James Orange in 1965, ‘Sing one more freedom song and you’re under arrest.’ Five hundred students promptly followed Rev. Orange to jail, singing all the way.”

– Former AFL-CIO President John Sweeney

Reverend James Orange played a critical role in actions that led to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and later applied his organizing skills in the fight for economic justice for workers across the south.“He was the living embodiment of the connection between the union movement and the Civil Rights movement,” former AFL-CIO President John Sweeney said in a 2008 tribute.

Born in 1942 to a large family, Orange grew up in Birmingham, AL, during a time when the city was an important focal point in the struggle for social justice.

The Orange family was actively involved in the fight for workplace fairness and racial equality. His father was fired in 1957 for participating in a union organizing effort at an American Cast Iron Pipe Company foundry, and his mother was a Civil Rights activist. The family often attended meetings at the city’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, which was a gathering place for the movement to end discrimination.

One church meeting set the course for Orange’s life. “I was a year out of high school,” he recalled about hearing Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a close associate of Martin Luther King, Jr., speak to the congregation in 1962. “The longer I listened, the more intently I listened, as I became absorbed in his message. It was 1963 and the movement was determined to break segregation in Birmingham,” he recalled.

Heeding the Call

After the services, Orange joined a group of young people at a meeting in the church basement to volunteer in the fight against Jim Crow laws, he recalled. “The trip down those stairs changed my life forever,” he said, “but there was no turning back.”

The next day he was arrested for picketing at a local store that refused to serve black customers, the first of more than 100 times Orange would be jailed for nonviolent acts of civil disobedience in the fight for social justice.

Orange soon became an important leader for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), organizing pickets and voter registration drives across the South despite constant threats from the Ku Klux Klan and the police. At the time, many African-Americans in the South were effectively denied the right to vote due to intimidation from election officials, poll taxes, and “literacy tests.”

His arrest in early 1965 for “disorderly conduct and contributing to the delinquency of minors” who were trying to register voters in the vicinity of Marion, AL, sparked fears that Orange would be lynched in jail. In response, Civil Rights activists gathered at a church for a prayer vigil and a protest march. The demonstrators “had hardly left the church, right in front of the courthouse and city hall, and they were brutally beaten,” he told the Clarion Ledger newspaper of Jackson, MS in 2007.

During the attack, an Alabama State Police officer shot and killed Jimmie Lee Jackson, a Vietnam veteran who was trying to protect his mother and gr

andfather from being beaten.

To seek justice for Jackson’s death, Civil Rights leaders planned a protest at the State Capitol, former SCLC president Charles Steele Jr. told The New York Times in 2008. “That became the march from Selma to Montgomery,” he added. National media coverage of the march that showed Alabama police gassing and beating peaceful protestors shifted public opinion about the Civil Rights movement and led to Congress passing the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices.

With King

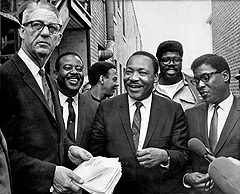

“Orange went on to become one of King’s top aides and followers of his principles of non-violence,” an AFL-CIO tribute notes. He played key roles in Civil Rights actions in Selma, Memphis and Chicago, where the 6’3,” 300-pound gentle giant persuaded street gangs to practice nonviolent civil disobedience.

“It’s true, he was gentle,” recalled Heather Gray, a longtime friend and radio-show producer in Atlanta. People were drawn to him by his “wonderful laugh and a singing voice that projected everywhere, which he used frequently at his church or for protest chants,” she added. But “in no way did his gentleness and kindness belie his passion for justice.”

Orange was standing below the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when King was assassinated there on April 4, 1968.

Union Work

By 1970, Orange had become a Baptist minister and settled in Atlanta. He continued his work with SCLC until 1977, when he helped gain union recognition and better benefits for members of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union at J.P. Stevens factories.

Workers there earned about 40 percent less than the industry average, and previous unionization efforts had faltered due to the company’s intimidation tactics and other flagrant violations of labor laws.With strong support from the AFL-CIO and civil rights leaders, the union launched a widely publicized national boycott that in 1980 convinced the textile company to sign union contracts covering 3,500 workers at 12 of its mills.

After that success, Orange worked as AFL-CIO organizer in Atlanta, applying King’s teachings to help empower working people. “He understood at his core what Dr. King taught — that Civil Rights without economic rights or justice was insufficient,” recalled former AFL-CIO Organizing Director Stewart Acuff.

For the next several decades, Orange led pickets, rallies, marches and protests for workers rights.“ Workers in poultry plants, sewing factories and shipyards all marched with him,” the AFL-CIO notes. “He was a fixture on organizing efforts in the South, playing a role in nearly every major effort by Southern working men and women to form a union or stand up for justice over the past several decades.”

In 1998, Orange was active in the AFL-CIO’s efforts to organize more than 16,000 hotel industry workers in New Orleans. Organizers of the campaign — which was aimed at housekeepers, banquet waiters, and laundry room employees, many of whom were working for wages that kept them below the poverty line — employed strategies used by the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, The New York Times reported.

In 2003, Orange helped organize the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, a two-week campaign that highlighted immigrant workers’ struggles for justice and shed new light on the exploitation of undocumented workers. Thousands of workers and social activists traveled more than 20,000 miles and led organizing drives in more than 100 cities. The drive was modeled after the Freedom Rides of the 1960s to defeat racial segregation in the South.

Orange also found time to keep up his civil rights work. In 1994, he led voter registration and education efforts in South Africa’s first post-Apartheid democratic elections, and he was a key organizer of Atlanta’s annual marches in memory of Dr. King.

Orange retired in 2005, but remained active in social justice efforts until he died on Feb. 16, 2008. He was 65.