Sanitation Workers’ Strike Spurs Cause of Economic Justice

December 31, 2004

(This article was first published in the January/February 2005 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

During a heavy rainstorm on Jan. 31, 1968, about two dozen Memphis sewer workers — all of them black — were sent home without pay. Their orders came from supervisors — all of them white — who were paid for their day’s work.

The next day, two black sanitation workers were crushed to death by a malfunctioning compactor in an accident attributed to standard operating procedure during inclement weather.

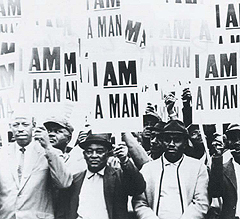

The response to formal protests about these outrageous employment practices came about two weeks later. On Feb. 12, workers learned that virtually nothing was being done about their fallen comrades and that they would be compensated only two hours’ pay for the full day missed in January. More than 1,000 black municipal employees walked off the job in a wildcat strike, demanding union recognition.

Marching Through Memphis

The walkout drew scant national attention at first, even among Civil Rights activists and labor leaders. But workers stayed off the job and their noisy demonstrations in downtown Memphis and around City Hall soon made the nation take notice.

Mayor Henry Loeb III took a hard line. A municipal strike was illegal, and he announced that he would not negotiate unless the sanitation employees went back to work. Loeb was unequivocal: He was not about to become the first Southern mayor to negotiate with a black municipal union. He offered raises and improved benefits, but he would not consider union recognition.

The activists tried to work around the mayor. About a week into the strike, more than 1,000 strikers and supporters attended a meeting of the city council: A rumor had spread that the Public Works Committee would vote to recognize the union and approve the deduction of union dues from workers’ paychecks. But the full council instead declared the strike an “administrative matter” and put it back in Loeb’s hands.

The council action resulted in a massive departure from City Hall and an impromptu march — the largest yet — along Main Street to Mason Temple, a large building that had become strike headquarters. The marches soon became a daily feature in Memphis.

The ‘Poor People’s’ Connection

At the time, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was organizing a “Poor People’s Campaign.” King’s plan was to stage a massive nonviolent act of civil disobedience on the streets of the nation’s capital (scheduled for April 22). The uprising by the working poor in Memphis, with its intertwining racial and economic themes, presented an opportunity to push the Civil Rights movement in the direction King felt it needed to go.

In Memphis, more than half of the black residents were living below the poverty line in 1968, compared with only one out of seven whites. Four out of 10 sanitation workers qualified for welfare, and they received no medical insurance, workers’ compensation, or overtime pay. They also lacked simple amenities such as a place to shower.

The workers wanted not just improved conditions, they wanted a union. Worker T.O. Jones had been trying to organize for the State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) for five years.

King, meanwhile, had long been arguing that unions had failed to reach poor people – organized labor had not gone beyond the ranks of well-paid, blue-collar industrial workers, he said, and had not begun to address “economic inequality.”

The inequity was keenly felt in American cities, particularly in the South. Low educational levels had left many blacks with few choices beyond unskilled labor. But in factories and on farms, such jobs were being mechanized out of existence. And as the numbers of rural workers fleeing the shrinking farm economy increased, unskilled labor opportunities in the cities diminished.

King’s First Appearance

When the strike was about a month old, King was traveling through the South as part of a “People-to-People Tour” to recruit for the rally in Washington. On March 18, while in Mississippi, he made a side trip to Memphis.

More than 10,000 workers, preachers, homemakers, and students greeted King at Mason Temple. It was obvious that the large black community was solidly behind what was essentially a labor organization drive. Poor black garbage collectors were five weeks into a strike and asking a racist city government not just for decent pay, but for a collective bargaining agreement. They also were asking for a place in the union movement.

“There is something wrong with the economic structure when you work and are still in poverty,” a striker said in a national interview. “It’s time people woke up to this.”

“Don’t worry about what’s happening to the workers,” said another. “Worry about what happens if the workers don’t win.”

Such remarks led King to conclude that if local blacks could make a city deal with poor sanitation workers, maybe his national movement could force Washington to deal with all of America’s poor. “You are doing here in Memphis what I am trying to do nationally,” King said. “You are reminding America that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.” At the March 18 rally, he called for a massive demonstration on March 22, urging black workers in the city to plan to boycott their jobs that day.

King’s appearance boosted morale: Not only had more than $5,000 been collected during his speech, but striking employees who had gone back to work agreed to re-join the job action.

International and national unions suddenly offered increased support. King announced he would not only take part in the March 22 rally, he would lead it.

Back to Memphis

A blizzard on March 21 shut down the entire city. Seventeen inches of snow clogged the streets, and there were no sanitation workers on the job to help clear them. The march was rescheduled for a week later.

The March 28 rally began late, with King leading 6,000 people in a walk from Mason Temple to City Hall. At the back of the slow-moving line, a group of teenagers began smashing windows and looting stores. King became aware of the events and tried to get the entire demonstration called off. But before it was over, 155 stores had been damaged, 60 people had been injured, and a 16-year-old boy had been slain by police gunfire.

A dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed, and more than 3,000 National Guardsmen were sent in by the governor of Tennessee. A day later, while King’s staff and local activists were being blamed for not properly planning for the event, about 300 sanitation workers and their supporters marched peacefully — and silently — under the watchful eye of five armored personnel carriers, five jeeps, three large military trucks and dozens of Guardsmen with bayonets fixed.

King announced that he would be back for a “massive nonviolent demonstration” on April 4. He was more certain than ever that Memphis had become crucial to the “Poor People’s Campaign.”

King returned on April 3. His staff and local officials met during the day and everyone agreed to postpone the march to April 8. A pre-march rally the evening of April 3 was not to be delayed, and that is when King delivered what become known as “The Mountaintop Speech.”

“You may not be on strike,” King said to the supporters of the sanitation workers. “But either we go up together, or we go down together.”

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. ... And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything.”

King was fatally shot the next day as he left his hotel room to go to dinner. He had re-energized a community movement and a strike, but only at a terrible cost. Days of rioting rocked America’s cities, although the reaction in Memphis was relatively subdued.

And on April 8, a march did take place in Memphis. A crowd estimated at 40,000 walked silently in memory of the fallen Civil Rights leader.

The Strike’s Legacy

President Lyndon Johnson and Tennessee’s governor pressured the city into recognizing AFSCME Local 1733 and allowing the check-off of union dues — key components that enabled the union to bargain over other grievances.

A signed contract in mid-April ended the strike two months after it began. Within 10 years, Local 1733 had grown from about 1,300 sanitation workers to more than 7,000 government employees, with jurisdiction in the fire commission, city courts, auto inspection stations, and city and county school boards.