Setting the Stage For the ‘Talent’ Unions

June 30, 2008

(This article was first published in the July/August 2008 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Among the catchphrases associated with the theatrical arts, “The Show Must Go On” is the most familiar. To workers, the phrase is more than a cliche: The longer-running the show, the more money to be earned.

Nowadays, all the world’s a stage: Performances are set up, staged, recorded, rebroadcast, retransmitted — on radio, on TV, streaming over the Internet or via cell phone, maybe even through a “product” such as a DVD or a video game.

Performers, of course, feel they should always be paid for their contributions, which are made regardless of whether a performance is “live.” But with the evolution of new media, it’s not always clear what the product is. And as the 100-day Writers Guild of America strike demonstrated, the issues are as murky as the products.

Broadcast, Then Recordings

Until the invention of broadcasting (and later, recording), the stage was the thing, and managers — often actors themselves — ran the show. Then, in the 1920s, the first radio networks were launched. Performances could be staged in one place and simultaneously distributed to far-flung audiences.

To accommodate audiences tuning in from different time zones, live broadcasts in New York were performed two or three times in one evening. And, as in a live stage show, the “talent” that provided a voice was paid for each performance.

In the late 1930s, audio “transcription discs” became available. Before these discs could be mailed out to stations that were not on the “live network,” a quality-check was run, with performers often asked to redeliver their lines. They were ordered to “stand by,” and were paid for a second performance, even if a re-do wasn’t necessary. The standby payments were the first “residuals.” They soon became the heart of any negotiation with performers.

Behind the Scenes

The first union in the industry was a stagehands union, the Theatrical Protective Union of New York, formed in 1886. These workers secured $1-a-day wages in a few key venues, and even won a strike or two. By 1894, the TPU (later IATSE, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) received a charter from the American Federation of Labor. Two years later, performers took the cue from the stagehands and the Actors National Protective Union was chartered.

The first union in the industry was a stagehands union, the Theatrical Protective Union of New York, formed in 1886. These workers secured $1-a-day wages in a few key venues, and even won a strike or two. By 1894, the TPU (later IATSE, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) received a charter from the American Federation of Labor. Two years later, performers took the cue from the stagehands and the Actors National Protective Union was chartered.

Major producers were also joining forces, forming a “Theatrical Syndicate” that gave them control of theater bookings in all the big cities. The syndicate made business tough for actor-managers such as Francis Wilson, who gave up and focused on the performance side. He would be the first president of the Actors’ Equity Association, which was formed in 1913 with Frank Gillmore as its executive secretary.

In early 1919, a few fledgling actors unions merged under one AFL charter, the Associated Actors and Artistes of America. The “Four A’s” first act was to issue a local charter to the Actors’ Equity Association.

Screen Tests, Radio Days

In 1920, as the motion-picture industry was starting to attract top talent, Equity’s Gillmore, with the AFL’s blessing, travelled to Hollywood and got the struggling Motion Picture Players Union (MPPU) to relinquish its charter. Throughout the 1920s, he took four-day train rides to Los Angeles (and back) in attempts to get the motion-picture producers to recognize Equity as the bargaining agent for silent-film players. Gillmore’s work was the foundation for the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), which was chartered in 1933.

In 1920, as the motion-picture industry was starting to attract top talent, Equity’s Gillmore, with the AFL’s blessing, travelled to Hollywood and got the struggling Motion Picture Players Union (MPPU) to relinquish its charter. Throughout the 1920s, he took four-day train rides to Los Angeles (and back) in attempts to get the motion-picture producers to recognize Equity as the bargaining agent for silent-film players. Gillmore’s work was the foundation for the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), which was chartered in 1933.

At about the same time, radio performers in Los Angeles trying to create a Radio Actors Guild merged with an independent New York group to form a “radio equity,” the American Federation of Radio Artists. (Like Actors Equity, AFRA was chartered by the Four A’s.) In 1938, with the support of radio stars such as Jack Benny and Bing Crosby, AFRA members negotiated the first collectively bargained agreement with the two national networks, NBC and CBS.

The Picture Players

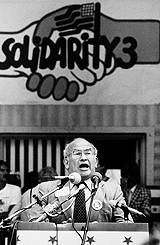

In 1941, Warner Bros. contract player Ronald Reagan went to his first SAG meeting, as an alternate. His wife, Jane Wyman, was elected to the board a year later and, in 1946, Reagan was elected 3rd Vice-President and was active in a series of strikes. In 1947, after being nominated by Gene Kelly, Reagan was elected SAG president.

He was re-elected to four successive one-year terms, and stayed on the SAG board — with his second wife, Nancy Davis, serving along with him — throughout the 1950s. The historical reviews of Reagan’s work as a union leader are mixed, though, clearly, he had the support of his peers. (An anti-labor image, however, is sealed forever by his actions barely six months into his first term as U.S. president. To the surprise of even some close advisors, Reagan fired 15,000 federal air traffic controllers striking over health-and-safety issues.)

With television on the rise, in 1950 the Four A’s created the Television Authority, which bargained the first TV contract. Two years later, the Television Authority and AFRA merged to create the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA). In 1956, AFTRA negotiated a formula for “replay performances” on syndicated TV. Four years later, AFTRA and the Screen Actors Guild members conducted their first joint negotiations, on TV commercials.

SAG and AFTRA have peacefully co-existed through the years, with the essential feature of their contracts being a union shop and the enforcement of residual payments. The union shop is always key: Since broadcast and recording began, “talent” unions’ members have relied on residuals for a good share of their income. The main incentive to join an actors’ union has been to be paid residuals — it’s a simple fact that if there’s no union, there’s no guarantee of residuals.

SAG Today

Many notable actors have been elected president of SAG, including Jimmy Cagney, Charlton Heston, Ed Asner, and Patty Duke. All the big-name stars are counted among its 120,000 members. But according to some estimates, two thirds of the members earn less than $1,000 a year from acting. A “middle class” of approximately 6,000 members earn enough to qualify for the union’s health insurance, but less than $100,000 a year.

Many notable actors have been elected president of SAG, including Jimmy Cagney, Charlton Heston, Ed Asner, and Patty Duke. All the big-name stars are counted among its 120,000 members. But according to some estimates, two thirds of the members earn less than $1,000 a year from acting. A “middle class” of approximately 6,000 members earn enough to qualify for the union’s health insurance, but less than $100,000 a year.

The middle-class actors are being squeezed out of opportunities by the increased reliance on low-budget reality shows. Meanwhile, fewer TV shows are enjoying repeat runs, with streaming videos on the Web more likely than conventional reruns. The studios have proposed a pay structure for streaming, and SAG is not happy with the formula.

SAG’s president since September 2005 is Alan Rosenberg, known best perhaps for roles in “L.A. Law” and “Cybill,” and for being married to Marg Helgenberger, star of “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.”

Will Actors Follow the Script?

The writers’ strike that ended in February appears to address all the aspects of new media: It codifies Writers Guild jurisdiction; expands their rights in all areas of content; and establishes residual payments for new-media reuse of covered material, including Internet downloads and ad-supported streaming of feature films and TV programs. It also creates what the Guild hopes will be “meaningful” auditing tools for monitoring the development of new media markets.

At this writing, Hollywood is bracing itself for a job action that could be every bit as dramatic as the WGA strike. The contract between the movie-producers’ association and the screen actors was to expire June 30.

SAG has struck eight times in its 75-year history, with the last film-and-TV walkout in 1980. The management alliance has made it clear that it wants to use the writers’ deal as a blueprint. To virtually no one’s surprise, however, union activist-actors are not happy with the language regarding the formulae for determining their residuals.