The 'Strike for Better Schools'

September 30, 2014

Almost 70 years after a strike by St. Paul teachers, their battle holds lessons for today’s postal workers and other public employees: The educators didn’t strike only on their own behalf – they walked a picket line for better schools.

In 1946, the idea of a teachers’ strike was revolutionary. But in October that year, nearly 90 percent of St. Paul, MN, public school teachers voted in favor of a work stoppage.

Elmer Andersen, who served as Minnesota governor from 1961-1963, recalled how unimaginable the strike was. “I remember the strike keenly because it is inconceivable to people today what a shock it was then to have teachers go out on strike,” he said. “Teachers just didn’t do that – it would be like a priest picketing a church or a cathedral. It was just absolutely unheard of.”

The teachers faced the difficulty any striking worker contends with – getting by without a paycheck.

But for St. Paul’s teachers, the stakes were higher: Strikes by teachers and other public employees were illegal. And in the weeks before the walkout, the commissioner of education had threatened to fire anyone who took part. He also said strikers would jeopardize their tenure and state teaching certificates.

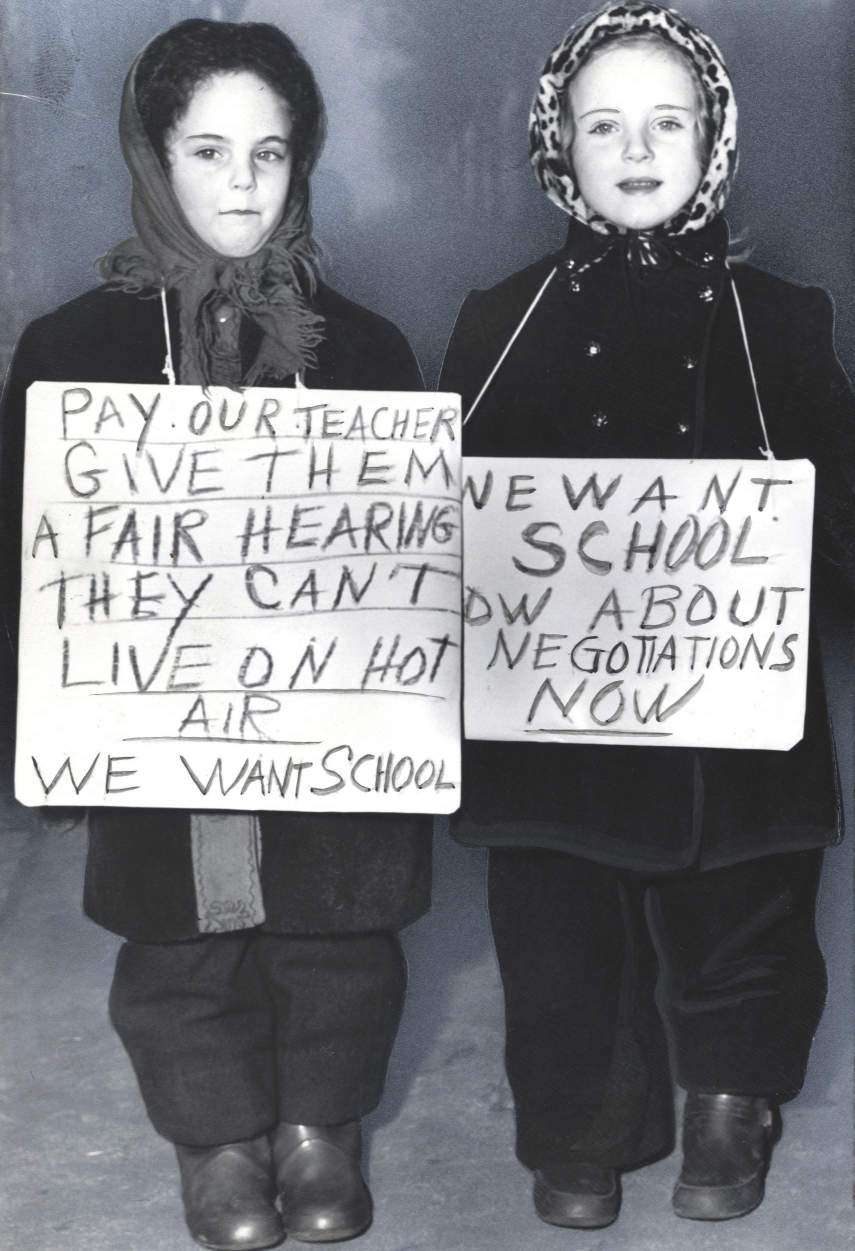

The day the strike actually began, just three days before Thanksgiving, the temperature was three degrees. Bundled in heavy winter clothes, teachers picketed at all 77 elementary and secondary schools.

And in the best of union traditions, they acted not only to improve their own lives, but also to help the children and families they worked for.

The strike lasted five cold weeks, ending on Dec. 27 in a victory for the beleaguered teachers.

Strike for Better Schools

Called the “Strike for Better Schools,” the job action exemplified public employees acting to benefit the public they served. And that was the key the strike’s success.

St. Paul teachers earned far less than their counterparts in similar cities, and the workers sought better pay. But they also demanded more.

- They sought smaller class sizes. St. Paul’s schools sometimes packed as many as 50 students in classrooms intended for 35.

- They demanded improvements to the city’s long-neglected schools, where walls crumbled and some primary schools had just one bathroom each for hundreds of boys and girls.

- They sought an end to the practice of requiring students to purchase their own textbooks. (Teachers frequently bought books for children whose families couldn’t afford them.)

Most importantly, the workers sought broad, long-term changes in how the city funded its public schools.

Like the schools in many cities, St. Paul’s schools lacked a stable source of funding. And in 1946, city departments operated under a WWI-era per capita spending limit. The teachers had to scrap for funds with every other city agency. At the same time, many families sent their children to parochial and private schools.

Amendments to change the funding system were routinely defeated because residents refused to spend more tax money on public schools and businesses pushed to minimize property taxes.

The problems of St. Paul’s schools were clear. The teachers’ strike offered a solution.

Solidarity Wins Out

The teachers’ public-minded agenda helped win support far beyond the city limits. The United Mineworkers were on strike at the nation’s coal mines at the same time and cutting supplies of electricity, but the St. Paul teachers strike was page-one news in cities from California to New York.

Many expected time and brutal Minnesota weather to break the strikers’ spirit, so officials made no effort to operate the schools. But unity held as the city’s parents, students, businesses, and private citizens of all kinds carried coffee and doughnuts to the picketers or invited them indoors to eat, drink and get warm.

Parents of students at Maxfield, Crowley and Marshall schools set up their own picket lines in sympathy with the strikers, and in many instances, students carried banners alongside their teachers. Many local unions offered support and put pressure on public officials to settle the strike.

Members of the School Engineers and Janitors Union Local 697 refused to cross the teachers’ picket lines. The St. Paul Trades and Labor Assembly passed a resolution in support of the teachers, who were not affiliated with the organization at the time.

Finally, a Solution

Finally, in late December, the city’s charter commission approved an amendment designating $18 per capita for schools and $24 per capita for all other city departments. On Dec. 27, the teachers suspended their strike.

In the months following, voters adopted an amendment to the charter that increased school funding.

Money finally became available for badly needed improvements to school buildings. Lobbying by strike leader Lettisha Henderson and others persuaded the Minnesota legislature to pass a law requiring school districts to buy textbooks for students to qualify for state aid. And finally, 19 years later, legislative efforts led to the establishment of an independent school district in St. Paul in 1965.

Nearly 70 years have passed since 1,165 teachers braved the frozen streets of St. Paul to make their community a better place. Their strike improved their own lives and the lives of the children and parents they served.

Sources: Sixty Years Ago, A Strike for Better Schools, by Michael Moore, based on the work of Cheryl Braunworth Carlson for her Ph.D. dissertation, and ‘Strike for Better Schools,’ – The St. Paul Public School Teachers’ Strike of 1946, published by Workday Minnesota.

Women Making Labor History

In 1946, women occupied a unique place in America’s workforce. They were well entrenched in teaching and other traditionally “female careers,” but just-ended WWII had created something entirely new. In the war years, “Rosie the Riveter” symbolized the tens of thousands of women who joined the highly unionized industrial workforce for the first time.

Although the St. Paul Local of the American Federation of Teachers had a long record of member activism, two women stood out as leaders of the historic strike.

Mary McGough, who was nearly 60 when the strike began, started teaching in St. Paul in 1903. She was an original 1918 member of the St. Paul Local and had served as an AFT national vice president.

Her forceful, articulate radio broadcasts were cited as a major factor in efforts to settle the strike. One striker remembered that McGough could “cut politicians to threads” and do it “in a very ladylike fashion.”

Lettisha Henderson was the strike committee chair and, at the time of the strike, a vice president for the AFT. Called a “tell it like it is” leader, she also was unconventional – a chain smoker in a day when very few women smoked, and a woman who did not wear hats, as was the custom at the time.

Together, McGough and Henderson were an effective team. Margaret Kelly, a longtime member of Local 28, said “Lettisha made the snowballs and Mary threw them.”