Union’s Anti-Discrimination Stance At Heart of WWII- Era Transit Strike

December 31, 2003

(This article first appeared in the January/February 2004 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

For five tense days in august 1944, a renegade faction of Philadelphia’s transit workers brought the city’s 2,600 trolleys, buses and trains to a standstill. The wildcat strike – staged to keep Black workers out of higher skilled jobs — was broken only after federal troops were called in to get the city moving and to protect equipment, passengers, and the union members of all colors who opposed the strike.

In the early days of World War II, the privately run Philadelphia Transit Company had about 11,000 employees working under a collective bargaining agreement, including just over 500 Blacks. For several years, the NAACP had been pressing the PTC to allow Blacks to train for work as motormen, conductors, bus drivers, station clerks, and other higher-grade jobs.

The Black workers were rebuffed by PTC management, which claimed it was powerless in the face of a clause in the labor agreement with the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union. The contractual stipulation guaranteed that existing workplace “customs” would continue in force unless the PRTEU agreed to changes.

The union refused to agree to upgrades for Black PTC employees, even though the NAACP and workers’ representatives gave assurances that no white workers would lose seniority as a result of the upgrades.

War Manpower Commission

In early 1943, the Philadelphia mass transit operation, like many other U.S. employers, suffered from a labor shortage. It asked the War Manpower Commission, which had special powers to allocate the nation’s labor resources during World War II, for permission to hire 100 white males to operate its vehicles.

The WMC turned down the PTC, noting that to honor the request would violate President Roosevelt’s 1941 executive order that banned discrimination by “race, creed, color, or national origin” in the hiring, promotion, and pay practices of defense-related industries. The PTC, the WMC said, should fill those positions with Black workers.

Roosevelt’s executive order was prodded by Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph, who in 1941 had threatened to lead a massive civil rights march on the nation’s capital unless the president ordered an end to segregation in the military and an end to hiring discrimination in the workplace. While FDR failed to desegregate the military, he did establish the Fair Employment Practices Commission to develop anti-discrimination policies and to investigate complaints.

The march was called off, but the FEPC, merely an “advisory commission,” proved powerless in dealing with bias in the workplace. The War Manpower Commission, which had been created during the military buildup during early World War II, would take an important role in enforcing FEPC policies.

Company Concession

Told that it could not hire only white workers, the city transit system in November 1943 said it would upgrade some of its Black workers — but only if the PRTEU agreed. The union, however, refused to comply.

In January 1944, some 1,700 workers signed a petition stating, “We, the white employees of the Philadelphia Transit Corporation, refuse to work with Negroes as motormen, operators, and station trainmen.” They wanted their employer to honor the “customs clause” and keep Black workers in the lowest-paid occupations.

Meanwhile, two other unions were vying to replace the PRTEU, which was derided as a “company union” – the Transport Workers Union (TWU) and the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway and Motor Coach Employees of America (AASERMCA). A representation election was set for March 14, 1944. The winner of that election would become the exclusive bargaining agent for the contract set to expire in April. With the election and bargaining looming, the PTC took no action on the FEPC’s directives to end discrimination.

Competition Spurs Backlash

The TWU was affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which a few years earlier had broken away from AASERMCA’s parent organization, the American Federation of Labor. The CIO representatives in Philadelphia were outspoken about fair employment practices, while AASERMCA all but banned minorities from its ranks.

PRTEU, the company union, was accused of trying to incite a backlash vote. Near some union-representation-election voting booths, loudspeakers placed by either the employer or the PRTEU blared, “A vote for the CIO is a vote for the Negroes to get your jobs.”Prior to the election, racist messages traced to the Ku Klux Klan were posted on company bulletin boards and left on employee vehicles.

For its part, AASERMCA kept mostly silent on race. But it did accuse the TWU of being Communist, a charge often lodged against CIO affiliates.

The vote, however, was a resounding victory for the TWU, which received more votes than the other two unions combined. With the contract set to expire in April, the CIO affiliate began negotiating a new agreement. Contract negotiations lasted several months as the PTC continued to drag its heels, hoping that opposition to the FEPC’s workplace fairness directives would weaken the TWU leadership’s hand.

Labor Shortage Grows

In the middle of America’s involvement in World War II, a growing labor shortage prompted the Manpower Commission to strengthen the FEPC’s anti-discrimination directives. On July 1, 1944, the commission ordered that the hiring of workers in every industry throughout the nation be done in compliance with its policies.

The PTC-TWU negotiations were in their fourth month when, on July 7, the company posted notices that it would comply with the FEPC. Eight Black maintenance workers began training as motormen; they were set to begin operating streetcars on Aug.1.

In mid-July, posters started to appear that urged a strike to protest Blacks becoming motormen. On July 30, an openly racist group held a meeting to put a strike plan into effect. After the secret meeting, a group of white PTC employees fanned out across the city to urge their co-workers against reporting to work the next day.

By 4 a.m. Tuesday, Aug. 1, most of Philadelphia’s trolleys, buses, and subway were at a standstill. Though large numbers of office and maintenance workers refused to join the strike, the motormen set up picket lines at the PTC’s 150 car barns. By noon, the city’s transit system had stopped running.

TWU, FDR Strike Back

TWU’s leadership denounced the strike, blaming it on “a small clique of disgruntled, self-seeking people who do not represent the real sentiments of PTC employees.” On Aug. 2, 250 TWU members initiated a back-to-work movement but failed to overcome the pressures and threats that the strikers directed at other workers who failed to take a stand on the issue.

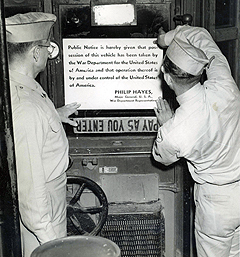

Late in the evening on Aug. 3, FDR ordered the Army to seize control of the PTC, restore transit operations, and enforce the government’s fair employment order. Noting that the WMC had designated Philadelphia as “a critical labor shortage area” vital to the nation’s war-production economy, Gen. Philip Hayes proclaimed that “delay in restoring full operations is measured in the blood of American soldiers overseas.” Still, the strikers refused to return to duty.

On the morning of Aug. 5, a Saturday, 5,000 armed troops took control of the transit system. The soldiers’ orders were to ride on PTC vehicles as guards and to replace civilian operators who were unwilling to work. The Army posted signs at all transit facilities that informed the strikers that they would be fired if they didn’t resume their normal duties by Monday, Aug. 7.

The notice said that violators would be denied employment anywhere for the duration of the war, and would lose their draft deferments. The strike ended the next day, with a majority of PTC workers signing pledge cards to return to work.

The transit system resumed “normal” operations the following Monday, except that federal troops continued to ride along to protect equipment and Blacks working as motormen. That same day, the PTC signed the contract that the TWU had proposed at the end of June. The CIO affiliate had negotiated an agreement without the “customs clause” and that gave substantial wage increases to PTC workers.

Aftermath

Some observers at the time believed that the transit company’s reluctance to agree to the upgrades was part of a strategy to weaken the TWU during contract negotiations. Management clearly preferred its relationship with the company union to the demanding bargaining style of the TWU, and was thought to be quietly encouraging the strike through leaders of the PRTEU. The NAACP’s Crisis magazine wrote that the PTC was in no hurry to end a situation that it thought was “unfavorably spotlighting both the CIO and the upgrading of Negroes.”

In the end, the workers’ lot was improved, and the NAACP and other community leaders were credited with helping to prevent a full-scale race riot. The strikers themselves, having learned that there was much less public sympathy for their position than they had expected, went back to work without any significant incidents.

Poll results showed that most Philadelphians supported the upgrades for Black workers and were overwhelmingly against the job action. “It would be hard to find in the whole history of American labor,” the New York Times editorialized, a strike in which so much damage has been done for so base a purpose.”

The 1944 Philadelphia transit strike was a milestone in the battle against race discrimination in the workplace. It was a great victory not just for Black workers, but for the white workers who stood with them.