Ralph Fasanella: Self-Taught Artist Chronicled Workers’ Lives

April 30, 2008

(This article was first published in the May/June 2008 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

“I didn't paint my paintings to hang in some rich guy's living room.” – Ralph Fasanella

By the time he started painting pictures at age 31, Ralph Fasanella had developed a strong disdain for the social and economic injustices he witnessed every day in the streets of New York City. Over the rest of his life, the self-taught artist created hundreds of paintings, most of which spread the union gospel and celebrated the dignity of the working people around him.

Like the workers around him, Fasanella labored in obscurity for many years. But he eventually was recognized as a great American artist, and one who spoke for workers everywhere. “He was a true artist of the people,” said AFL-CIO President John Sweeney, “in the tradition of Paul Robeson and Woody Guthrie.”

Tenement Beginnings

The third of six children, Fasanella was born in a Bronx tenement on Labor Day in 1914, and as a child he experienced all of the hardships that members of working families suffered between WorldWar I and the Great Depression.

His parents had emigrated from Italy to escape Mussolini’s fascism and to build a better life.His father, Joseph Fasanella, found work as an iceman, hauling the heavy blocks from a horse-drawn cart to the upstairs apartments in the neighborhood. His mother, Ginevra,made buttons in a dress factory.

The young Ralph Fasanella split his free time between helping his father deliver ice and accompanying his mother to union meetings and anti-fascist rallies. His family’s struggles to make ends meet left an indelible mark on his sense of justice and his political leanings, which are evident in many of the paintings he later created.

The family’s problems grew when Joseph abandoned them to return to Italy in the early 1920s. Ralph dropped out of sixth grade and wound up in reform school, where he developed contempt for the rigid social order of the day.

As a young man during the 1930s, Fasanella worked in the city’s garment factories and as a truck driver. He also was a member of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE Local 1227) in Brooklyn. He took full advantage of the educational opportunities his local provided, and took an active interest in union and civic affairs as the nation struggled through domestic and international turmoil. In 1937, the restless young man joined an American volunteer force fighting against the fascists during the Spanish Civil War.

After two years overseas, Fasanella returned to the U.S. and committed his efforts to the goals of the labor movement. As a union organizer in the early 1940s, he recruited firefighters, elevator operators, and hospital workers. He also led successful UE membership drives at General Electric, Sperry Gyroscope, and AT&T.

An Artist Is ‘Born’

By chance, Fasanella discovered his artistic talent in the mid-1940s. A friend suggested he take up painting as therapy for arthritis in his fingers. After a brief stint studying art part-time at a labor college, he became consumed by a passion for portraying the world he knew through painting.

“From the beginning, he approached painting the way he approached organizing — with empathy for and a great love for working people,” wrote Paul S. D’Ambrosio, author of Ralph Fasanella’s America.

Although he had left his job to paint full-time, Fasanella’s passion didn’t pay the bills, so he got a job at a gas station. In 1950, he married Eva Lazorek, a schoolteacher with whom he would raise two children.

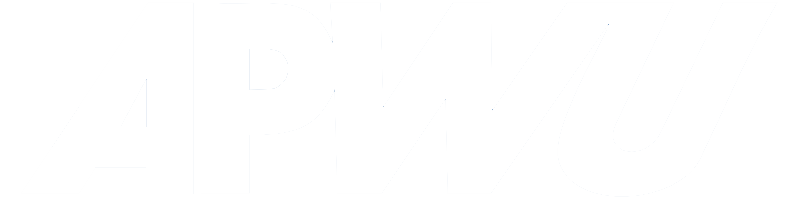

But Fasanella never stopped painting. His creations depicted workers’ everyday existence and he remained undiscovered for more than 25 years, in part because he was blacklisted by art dealers and galleries reluctant to pass along the political messages of his paintings. Labor leaders, art critics, and a few wealthy buyers took notice, but he continued to paint as an undiscovered amateur.

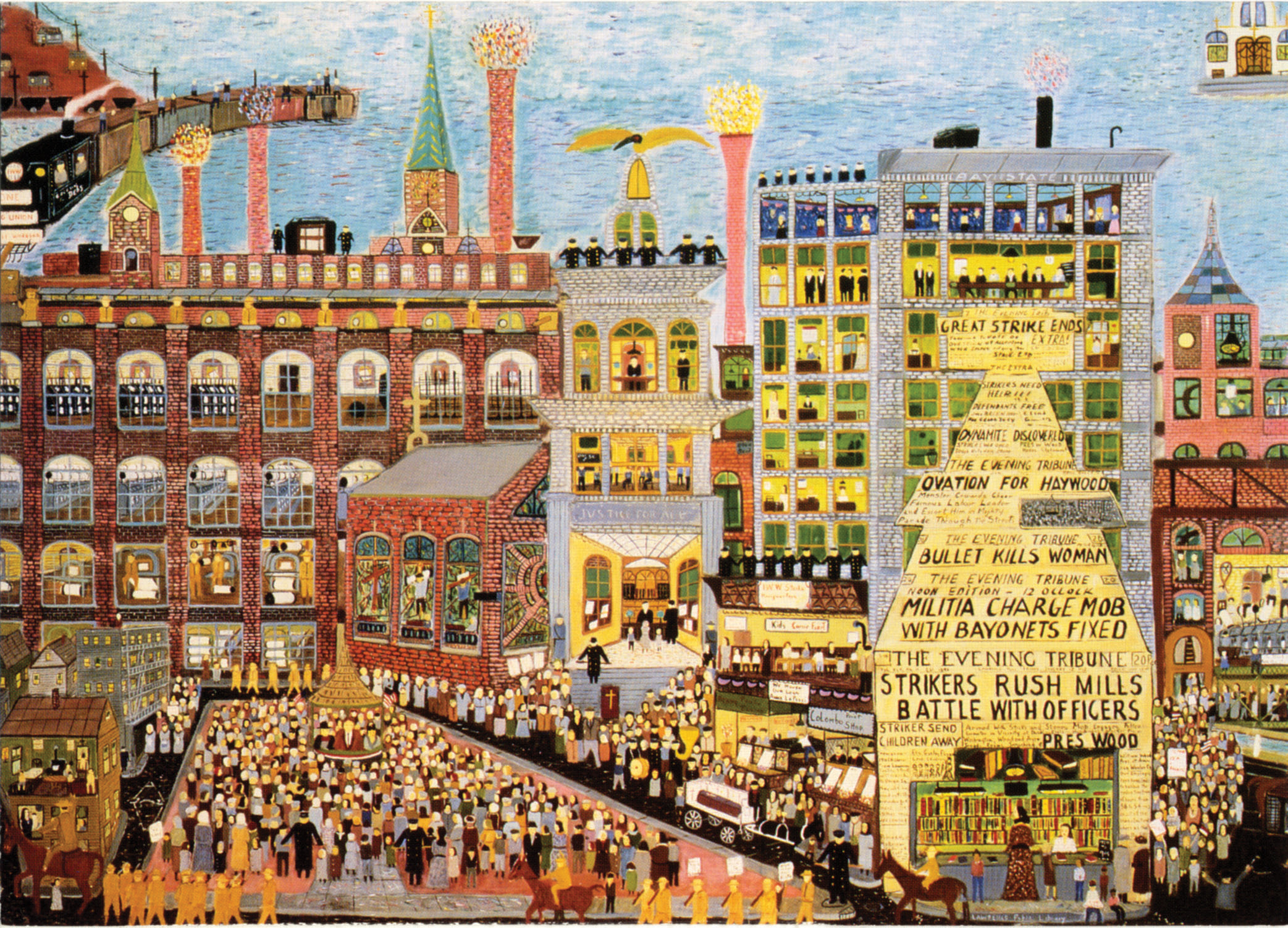

His colorful, highly detailed, and enormous canvases were filled with vibrant city scenes of the people he saw in everyday life, often at work, at job actions, or union meetings. Fasanella’s highly original style would come to be described as both “quasi-surrealist” and as “primitive school” folk art, but he scorned such labels, saying that his art “just came out of my belly. I never planned it.”

When one critic advised him to study Rembrandt’s methods, Fasanella responded, “[Expletive] you and Rembrandt! My name is Ralph.”

At Long Last, Recognition

Fasanella’s life changed dramatically with his Oct. 30, 1972, appearance on the cover of the weekly New York magazine, along with the headline, “This man pumps gas in the Bronx for a living.” Soon after, he appeared on the Dick Cavett Show and CBS Sunday Morning, and was being profiled in other media as well. Suddenly, his “working-class art” was being exhibited in galleries nationwide.

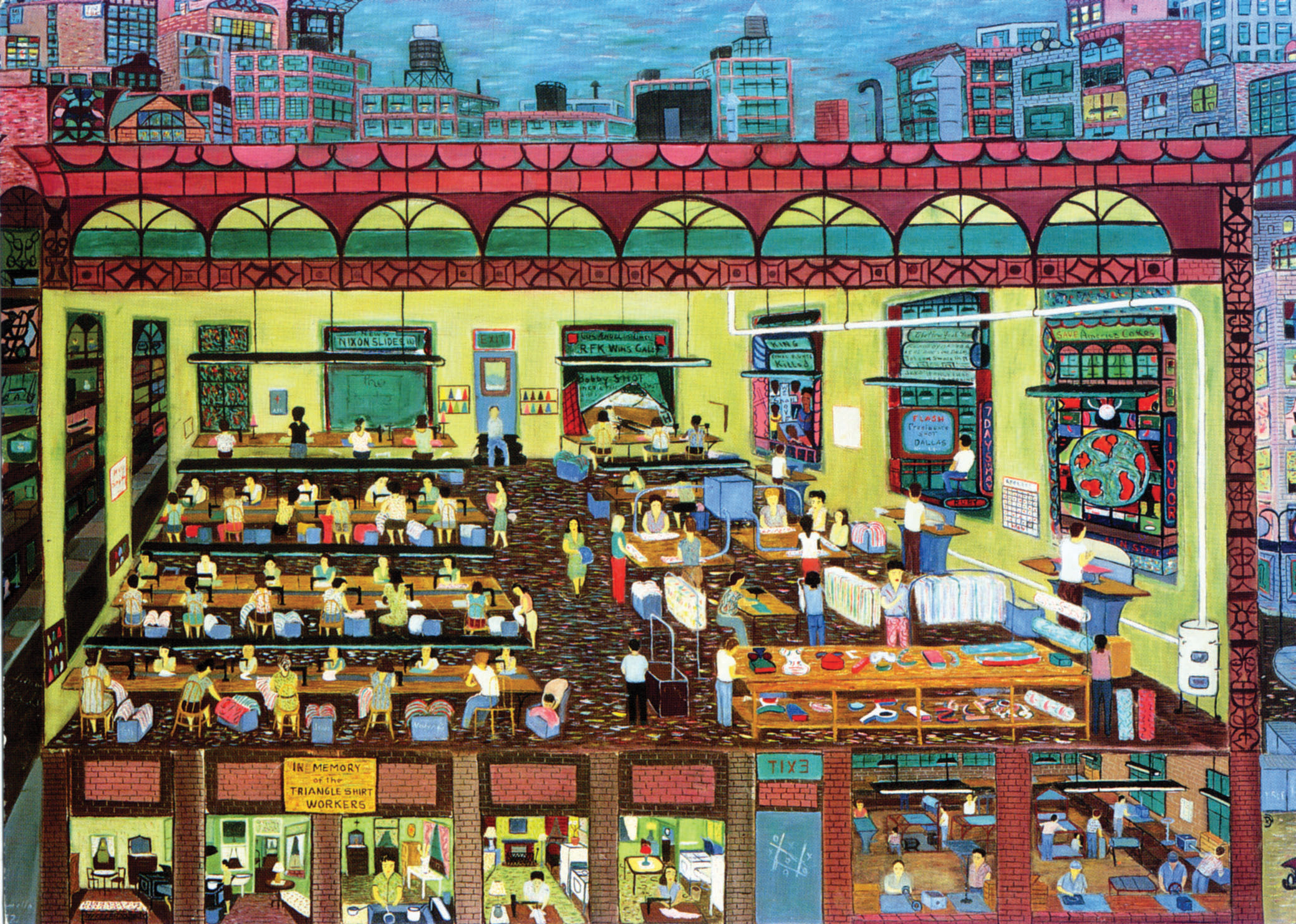

Despite the acclaim, Fasanella spent a few years living at a YMCA in Massachusetts while completing some of his most notable work, including several famous scenes of the 1912 “Bread and Roses” textile workers’ strike in Lawrence. He ultimately returned to New York, where for two decades he continued to portray urban settings and labor unrest. He died, in 1997, at age 83.

For more information, visit www.laborarts.org/exhibits/fasanella.