Groundbreaking, Heartbreaking ‘Harvest of Shame’

April 30, 2005

(This article was first published in the May/June 2005 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Half a century ago, the plight of the nation’s migrant farm workers was brought home to millions of Americans, many of whom had just enjoyed their biggest meal of the year.

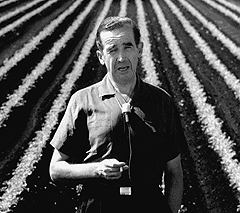

Harvest of Shame, a prime-time CBS documentary, was first televised on Thanksgiving Day 1960, confronting families throughout the country with a graphic exposé of the terrible working and living conditions of the men, women, and children who had put much of their holiday feast on the table.

“Meet your fellow citizens,” legendary broadcaster Edward R. Murrow told viewers at the beginning of the hour-long show. “These are the forgotten people — the under-protected, the undereducated, the under-clothed, the underfed.”

‘Other Side’ of the American Dream

Hidden from most Americans, migrant farm laborers worked long hours for as little as a dollar a day, returning at night to squalid grower-owned shacks that only rarely offered electricity or running water. Paid by the bushel or the bucket, their lives depended not just on how hard they worked, but on the vagaries of weather, crop yields, and the labor market itself.

Morrow traced the lives of farm laborers on both coasts as they worked their way north, following the harvest in America’s orchards and fields, then returning in late fall, invariably with little to show for their efforts. “I figure I broke even,” a worker tells Murrow’s production crew. “I left broke and I came home broke.”

One memorable scene shows 9-year-old Jerome King sitting on a bed, surveying the one-room cinderblock structure that is his family’s temporary home. His mother and older siblings are in the fields, and as he minds his three younger sisters, Jerome points out a hole in a bed that was made by a rat. Asked what he would feed his sisters that day, the boy shrugged, “I don’t know, sir.”

Jerome’s mother, interviewed in the field, said that she brought home $1 a day, and the farm nursery asked 85 cents to watch her kids. Another woman, identified only as “Mrs. Dobey,” explained that she could afford to give her children milk only one day per week — she expressed hope that her children wouldn’t end up like she did, but she doubted they would get as far as high school.

While Murrow pointed out that “hope lies in education” for the children of migrant workers, he noted that most states did not try to educate migrants and had no laws regulating child labor in agriculture. Only one in 500 migrant children finished even grade school.

As for the adults, Murrow pointed out that “farm labor is excluded from all federal legislation designed to protect the rights of those engaged in interstate commerce to organize and to bargain collectively.” In other words, union organizers were at an insurmountable disadvantage.

Reaction to ‘Shame’

Murrow brought a strong sense of indignation to the production, but many observers foundHarvest of Shame to be at its most powerful when the bosses spoke for themselves. “A lot of them don’t know any different,” said one grower. “They’re the happiest race of people on the earth.” Another boss said bluntly: “We used to own our slaves; now we just rent them.”

The program got many positive reviews. Walter Cronkite, a long-time colleague of Morrow, recently said, “the CBS News broadcast ofHarvest of Shame became one of the seminal moments when the country’s perception of itself seemed to shift... The film triggered a wave of social awareness and activism that came to define the 1960s.”

Morrow’s documentary left an indelible mark. Public outcry helped put the worker’s plight on the nation’s political agenda, and Congress and several state legislatures soon passed measures to provide healthcare and educational facilities for farm workers and their families.

But real progress was elusive. Agri-business interests launched an offensive and members of Congress from farm states blocked attempts at further reforms and wage increases.

Murrow’s program also proved to be a watershed event for the media. In the early days of television, during the 1950s McCarthy Era, producers refrained from vigorously questioning the established order, fearing a spot on a secret blacklist or a subpoena from the House Un-American Activities Committee. Harvest of Shame, however, boldly challenged vested interests and government policy makers. “Some 40 years later,” Cronkite notes, “ Harvest of Shame’s most lasting legacy may be the model Murrow and [executive producer Fred] Friendly created for a generation of broadcast journalists. It paved the way for those who wanted to expose wrongdoing, and gave voice to the most powerless members of society.”

Indeed, Murrow’s exposé ushered in a new era, in which the powerful visual impact of television helped build a case for the Civil Rights Movement and the War on Poverty. The program also fueled the movement to organize agricultural workers, leading to the successful California grape boycott led by Cesar Chavez and the creation of the United Farm Workers Union.

Migrant Labor Today

Despite a number of progressive laws passed in the aftermath of Harvest of Shame, far too many of today’s migrant farm workers are not much better off.

In December 2003, the Palm Beach Post published “Modern Day Slavery,” a series of investigative articles documenting the continuing struggles of migrant workers near the central Florida town of Immokalee, one of the communities Murrow visited in 1960. The newspaper found that on a good day a worker might make only $50 for 12 hours of picking tomatoes for Yum! Brands Inc., the owner of Taco Bell, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut, and other fast-food restaurant chains.

The newspaper’s investigation led to the conviction of three farm bosses for slavery, extortion and weapons charges. The bosses had threatened more than 700 workers with death if they tried to leave their “employment,” and assaulted some who tried to help. Several bosses were sentenced to as much as 35 years in prison and ordered to forfeit $3 million in assets.

There is some good news — Immokalee farm workers took matters into their own hands recently. In March this year, they conducted a 15-city “Taco Bell Truth Tour” to publicize the corporate greed that has held them down for so long.

Threatened with a nationwide boycott, Yum! Brands quickly agreed to meet the Coalition of Immokalee Workers’ modest demands. On March 8, the corporation said it would increase the amount it pays tomato pickers by a penny a pound and provide other improvements to working conditions.

Said Lucas Benitez, a founding member of the workers’ coalition, “Now we must convince other companies that they have the power to change the way they do business.”

Harvest of Shame will be re-broadcast on June 2 on the Discovery Times Channel.