1913 Silk Strike United Diverse Workforce

October 31, 2010

A 1913 strike among silk industry workers in Paterson, NJ proved that laborers could stand up to the factory bosses who exploited them. The strike united men and women, immigrant and native-born, and skilled and unskilled workers, and although it was not entirely successful, it left an enduring legacy. The strike inspired union leaders in other industries and set the stage for their victories in the decades that followed.

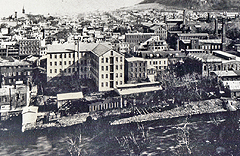

In 1794, the Great Falls of the Passaic River were harnessed in a network of canals and waterwheels designed by Pierre l’Enfant, a revolutionary war hero, to provide power for mills. Various industries were soon attracted to the site for its unique resource, as well as its close proximity to the ports and markets of New York City.

In the 1850s, silk weaving and finishing had eclipsed cotton, gun, and locomotive manufacturing as the town’s dominant industry, and Paterson became known as “Silk City.” By 1910, 75 percent of the city’s workers were foreign born, and more than one fifth of its 125,000 residents worked in the 300 large plants that produced nearly 50 percent of the nation’s silk goods.

Silk weavers and dyers were highly skilled workers, and most learned their craft in England, Germany, Poland, France or Italy. Women made up nearly half of the skilled workforce, yet they earned less than their male counterparts. Dyers’ assistants and other silk workers — most of whom were women and children — were considered “unskilled” and were paid even less.

Many unskilled workers were paid by the piece and had to bring extra work home to make a livable wage. All workers were expected to put in 10-hour days, plus an additional half day on Saturday, yet they still struggled to make ends meet — wages in Paterson were set well below what silk workers in other cities made.

By 1913, the workers organized more than 140 job actions by craft and by shop to resist wage reductions and changes in traditional work practices. Without an industry-wide union, however, the piecemeal gains they achieved were minor and temporary, as factory owners sought ways to squeeze more and more from the workers.

Strike!

On Jan. 27, 1913, when management at the Henry Doherty plant, one of Paterson’s largest mills, demanded its broad silk weavers double their output by operating four looms at time instead of two, 800 workers walked off the job. They were soon joined by ribbon weavers and dye-house workers. Seeking to form a lasting union to gain better pay and shorter hours for all, the silk workers formally chose representation from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The IWW (popularly known as the “Wobblies”) sought to organize all workers — regardless of craft, skill level, ethnicity, or gender — on an industry-wide basis. The IWW’s “One Union” philosophy was considered radical by most traditional craft unions and was widely condemned by conservatives as anti-American. But the unity it fostered in other job actions had been effective in countering companies’ efforts to pit ethnic and craft groups against each other.

Legendary IWW leaders “Big Bill” Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Carlo Tresca arrived in Paterson in mid- February to organize a worker-led central strike committee, strengthen unity among the various crafts and ethnic groups, organize pickets, and build community support. By the end of February, 24,000 workers had joined the strike, and Paterson’s 300 mills and dye houses stood idle.

The Bosses Respond

Mill owners refused to talk to the union and did all they could to break the strike. They transferred production to out-of-state factories and vowed to “starve” the workers back to the mills. On their side stood Paterson’s police and judges, who found reason to ban union meetings, confiscate literature, and arrest more than 2,000 strikers.

Undeterred, the strikers held meetings at the home of fellow silk workers Maria and Pietro Botto in nearby Haledon, NJ to keep workers informed, combat rumors, and boost morale with songs and skits as the strike dragged on through the spring.

Organizers called one mass meeting to urge workers to avoid responding to company and police tactics with violence. “Your power is in your folded arms,” Haywood said, after a union sympathizer was shot to death by a company security guard. “You have killed the mills, you have stopped production, you have broken off the profits. Any violence you may commit is less than this, and it will only react upon yourselves,” he said. Meanwhile, the IWW was working to raise funds to assist workers’ families and build public support. With help from artists, writers, musicians, and some wealthy supporters in New York City, the union organized a massive pageant at Madison Square Garden on June 7 to dramatize the silk workers’ plight.

The pageant earned international attention, but the funds it raised were not enough to pay for the strikers’ food and rent, and the workers’ solidarity began to crack. A group of higher paid workers instructed their representatives on the central strike committee to accept settlements with individual mill owners, and by mid June they returned to work.

In July, the strike committee voted to endorse shop-by-shop settlements and the strike was over, a defeat for the IWW. But while the company owners officially conceded nothing, they learned their unionized workers were a force to be reckoned with: Some employers shortened hours, and the two-loom system remained the standard in Paterson silk mills for years to come. In 1916 and again in 1919, the Paterson company owners recognized unions and made significant concessions on work hours rather than risk another strike.

A Lasting Legacy

“The workers didn’t go back to their jobs as the same people,” notes Evelyn Hershey, education director of the American Labor Museum and Botto House National Landmark in Haledon, NJ.

“Many had a newfound respect for workers in other crafts and from different ethnic backgrounds,” she added, “and many — especially the women — inspired leaders in many union battles to come.”

Perhaps most importantly, the Paterson silk strikers showed that workers can overcome ethnic, racial and gender differences to achieve solidarity, and they set the stage for future union victories in other industries.