‘Si, Se Puede,’ Yes, We Can

August 31, 2011

It is next to impossible to think of the modern labor movement — and the struggles of farm workers in the United States — without César Chávez. A firm believer in nonviolence, Chávez beat the odds and successfully organized a union of farm workers. In the process, he became a symbol of hope to millions of Americans.

César Estrada Chávez was born on March 31, 1927, in North Gila Valley in Arizona, near the California-Mexico border. His father, Librado, was a small farmer, and also ran a grocery store, garage, and pool hall with César’s mother, Juana. Chávez was the second child, with an older sister and three younger brothers.

During the Great Depression, when Chávez was 10 years old, the family was evicted from their farm — land that they had worked for nearly 50 years. “We left everything behind,” Chávez once said. “Left chickens and cows and horses and implements. Things belonging to my father’s family and my mother’s as well. Everything.”

After being evicted, the Chávez family was forced to become migrant farm workers. He recalled living “under a tree, with just a canvas on top of us, and sometimes in the car.” The family worked in Arizona and California, harvesting the fields. The work was hard, Chávez said, and the family often worked long hours with little access to food, clean water, or bathrooms. After completing the eighth grade, and attending 38 schools, Chávez dropped out and was forced to work the farms full-time because his father had been injured in a car accident.

Despite their hardships, the Chávez family never considered themselves “poor,” and they frequently put others before themselves. His mother often offered meals to homeless men and women, and as a teenager, Chávez and his sister helped other migrant farm workers by driving them to the hospital; they refused to accept money or gas in return.

In 1944, Chávez lied about his age so he could join the U.S. Navy. After serving for two years, he married his long-time girlfriend, Helen Fabela. To support his new wife, Chávez worked as a ranch hand for two years, then landed a job with a lumber company in San Jose, CA.

In 1944, Chávez lied about his age so he could join the U.S. Navy. After serving for two years, he married his long-time girlfriend, Helen Fabela. To support his new wife, Chávez worked as a ranch hand for two years, then landed a job with a lumber company in San Jose, CA.

Taking to the Fields

Life changed for Chávez when he was a young man working in the lumber yards: He met Fred Ross, a well-known community organizer. Ross had recently founded the Community Service Organization (CSO), a group that organized Mexican-Americans in California. With Ross’ training and encouragement, Chávez quit the lumber yard and became a full-time CSO organizer, setting up new chapters across California. In 1959, he was named CSO’s executive director — but Chávez resigned in 1962 after the organization denied his request to organize farm workers. He moved to Delano, CA, with his wife, their eight children, and a CSO colleague, Dolores Huerta, and established the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). Chávez refused to label the NFWA a “union,” he said, “because of the long history of failed attempts to create agricultural unions, and the bitter memories of those who had been promised justice and then abandoned.” He used the models of community service that he learned from the CSO to lobby for minimum wage, un-employment insurance, and collective bargaining rights for members.

In 1965, the plight of farm workers in California gained national attention when the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) went on strike after Delano grape growers cut workers’ pay during the harvest. The NFWA joined the strike, and, under Chávez’s direction, the workers brought attention to the struggle through non-violent means. The grape boycott brought together many groups that advocated on behalf of farm workers, and in 1966, AWOC, an AFL-CIO funded union, and other organizations merged to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, which would eventually become the United Farm Workers (UFW).

The strikers spoke out against their impoverished living conditions, and the movement spread to nine labor camps. The picket lines moved quickly from the fields where the grapes were harvested to the cities where they were sold. Union longshoremen and truck drivers refused to load or haul grapes, and students and activists also stood in solidarity with the farm workers. Volunteers urged consumers to support the workers by boycotting grapes; at the height of the action, 13 million Americans supported the workers. By 1969, the campaign had stopped Delano grape sales in Detroit, Chicago, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Montreal, and Toronto.

In July 1969, the organization’s efforts paid off: After three days of negotiations, the grape growers agreed to recognize the union, raise the workers’ pay, set up a labor-management committee to regulate pesticide use, and contribute to health and welfare plans for employees.

‘La Causa’

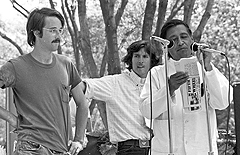

A student of the teachings of St. Francis and Mahatma Gandhi, Chávez was a firm believer that “non-violence could be an active force for positive change.” He often fasted to publicize causes and emphasize his non-violent approach. In 1968, during the grape boycott, Chávez’s conducted a 25-day fast as atonement for violence that had occurred during the strike. He agreed to end the fast on March 10, during a visit from Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who he had befriended when Kennedy investigated farm workers’ conditions two years earlier. Support from Chávez and other UFW members helped Kennedy win the California Democratic presidential primary several months later.

In the years that followed, the Chávez-led UFW became a powerful force on the political scene. The union helped Mexican Americans exercise their right to vote, and paved the way for many Mexican-Americans to hold office, shifting the political landscape in California.

In the 1970s, Chávez continued his fight on behalf of agricultural workers, and urged elected officials to join the cause. He backed Jerry Brown’s campaign for governor of California, and following Brown’s election, he convinced Brown to support a farm labor law that would give farm workers the right to union elections. After many demonstrations, registration drives, boycotts, and protests, the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) was signed into law in June 1975.

The passage of ALRA led to a series of UFW election victories; but eventually, Chávez withdrew from union organizing. He turned his focus to promoting awareness of farm workers’ struggles, and travelled extensively to promote the cause. He gained the support of the public during his campaign to draw attention to the dangers of pesticide use, a cause he spread through the use of direct mail, rather than by recruiting volunteers.

By the 1980s, the UFW was plagued with internal problems, and in 1992, had only 22,000 members. But Chávez remained a key figure in the Mexican-American community and in the labor movement. He successfully organized the first union for farm workers, and trained a generation to advocate for worthy causes through a non-violent approach.

Years before his death in 1993 in Yuma, AZ, Chávez was asked if he wanted to be remembered through public memorials. Chávez replied, “If you want to remember me, organize!”